How to use IFS and LET functions instead of nested IF statements in Excel

Nested IF statements used to be the go-to choice when dealing with multiple conditions in Microsoft Excel . But just because they get the job done doesn't mean they're the best tool for the job. Battling through endless parentheses and trying to keep track of which IF controls which result is as tedious as checking the numbers yourself. And if you try to look at the formula a week later, you'll struggle to remember why you set it up that way.

That's why you should stop stacking IF functions like Jenga blocks and start using IFS and LET functions in Excel. Combine the two, and what once looked like complicated lines of code becomes a set of clear instructions that you can actually maintain, share, and explain without difficulty.

Nested IF functions are bad, but IFS functions are better

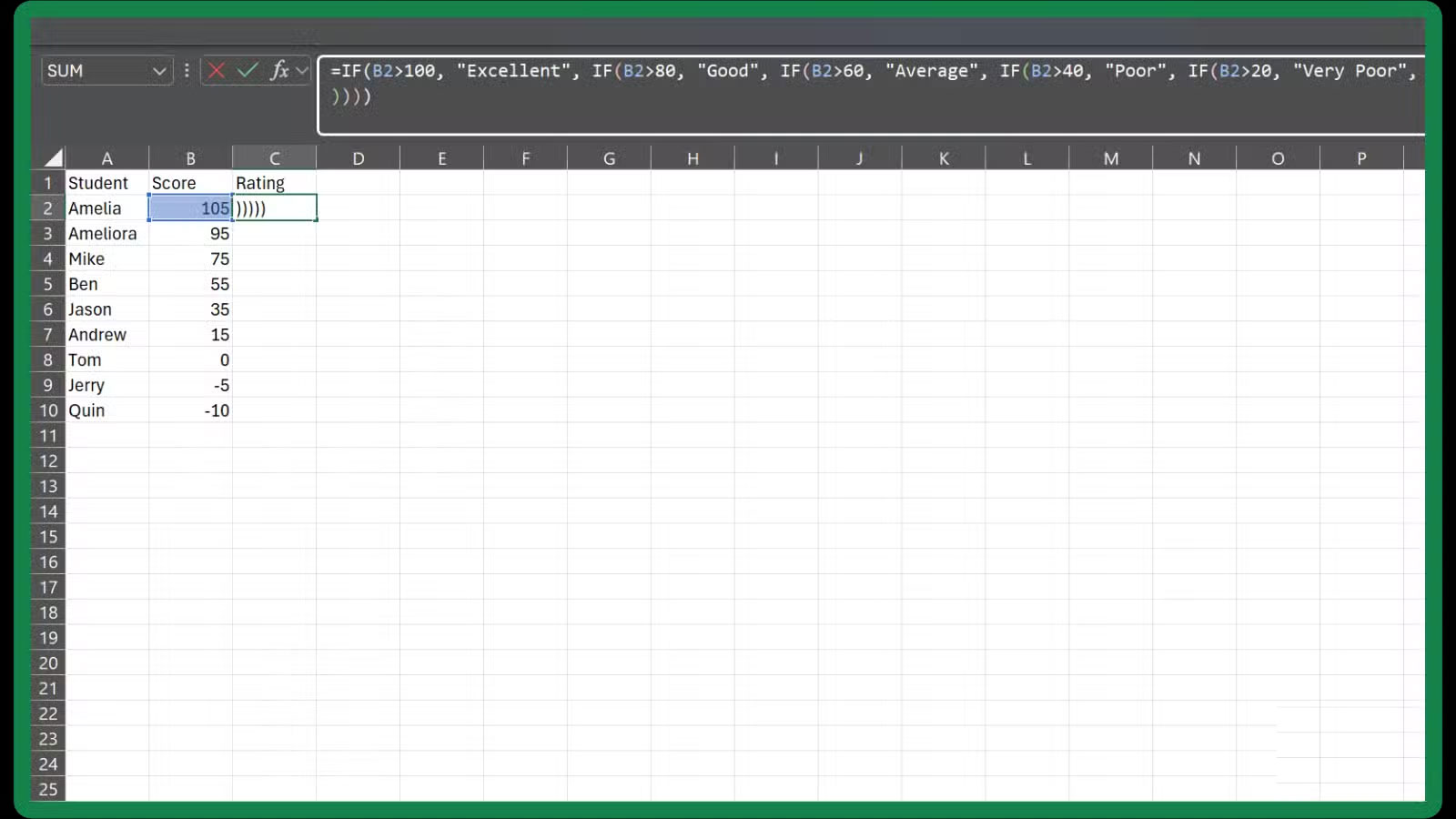

When you only need two results, the IF function is fine. But as soon as you start stacking conditions (if this, then that, if not then this, then that), things get messy. It works at first. But if you've spent any time working with real business spreadsheets, you know how quickly it gets confusing:

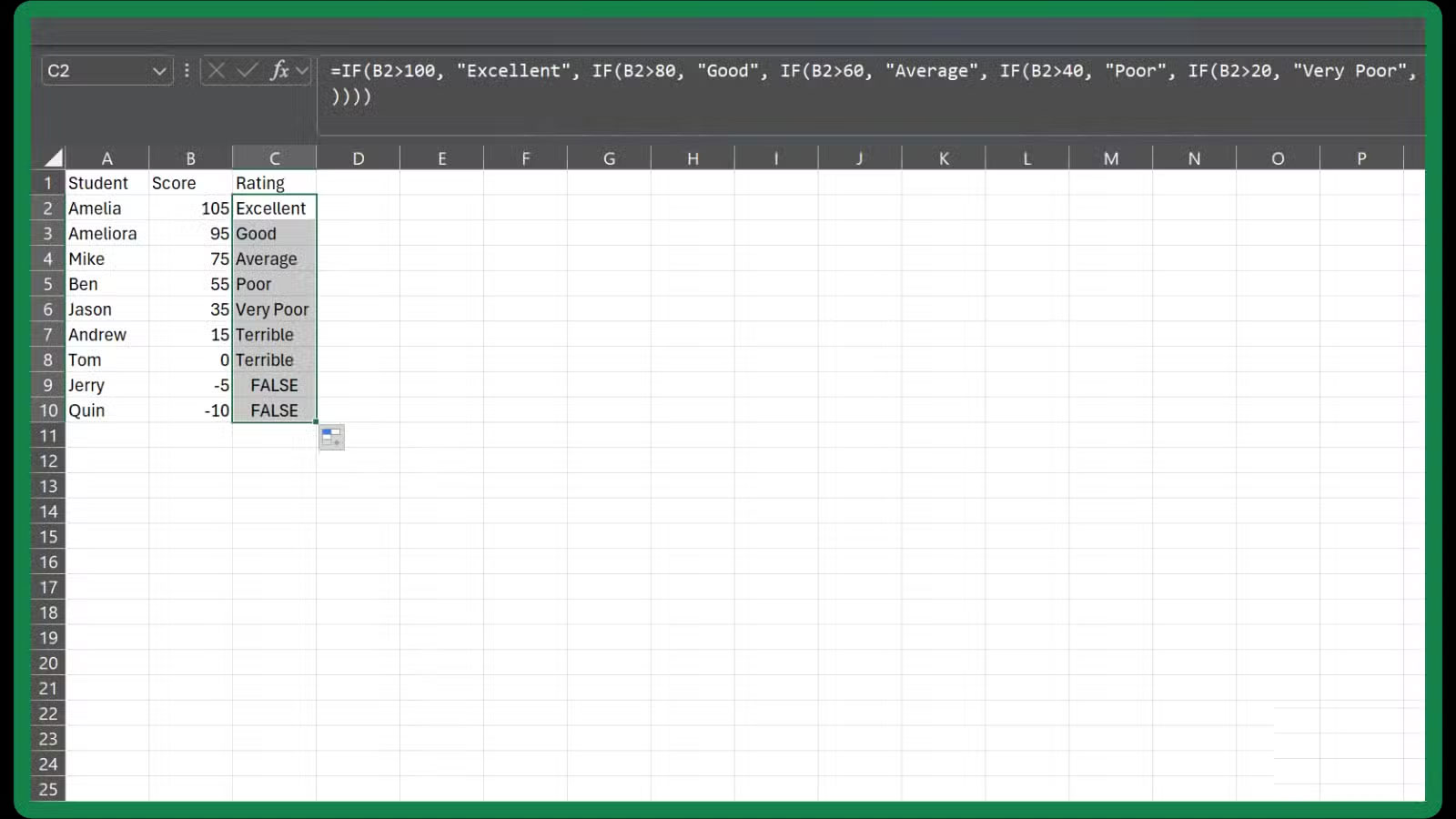

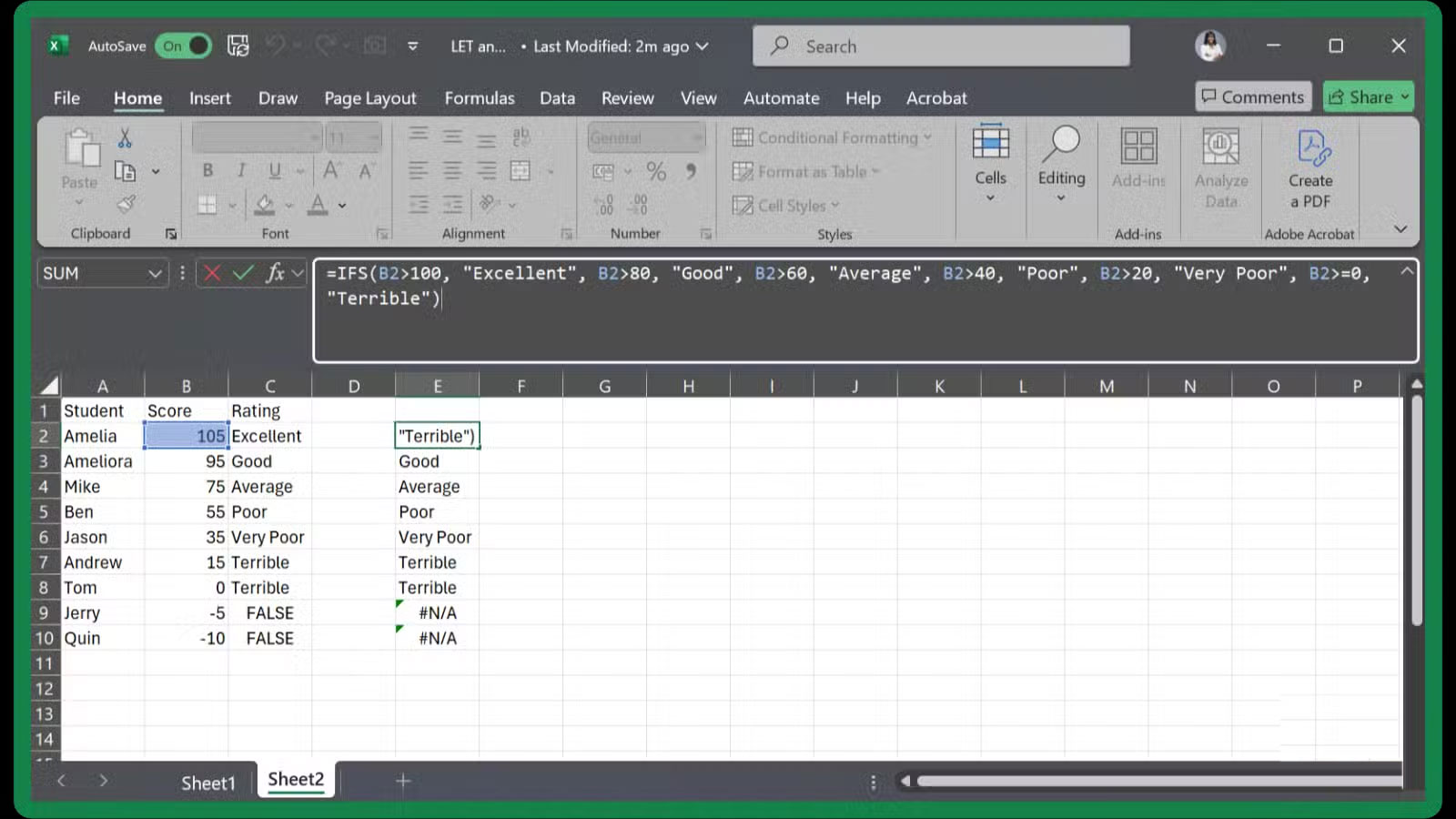

=IF(B2>100, "Excellent", IF(B2>80, "Good", IF(B2>60, "Average", IF(B2>40, "Poor", IF(B2>20, "Very Poor", IF(B2>=0, "Terrible"))))))Technically, Microsoft allows you to nest up to 64 IF functions. But if you get close to that limit, you won't know how to stay sane, because the trouble spots add up very quickly.

First, try looking back at that nested IF formula 6 months later and understand what it means. Good luck finding the right place to add another condition without accidentally breaking the whole chain. If you accidentally miss a parenthesis later, you'll spend an hour trying to figure out what went wrong.

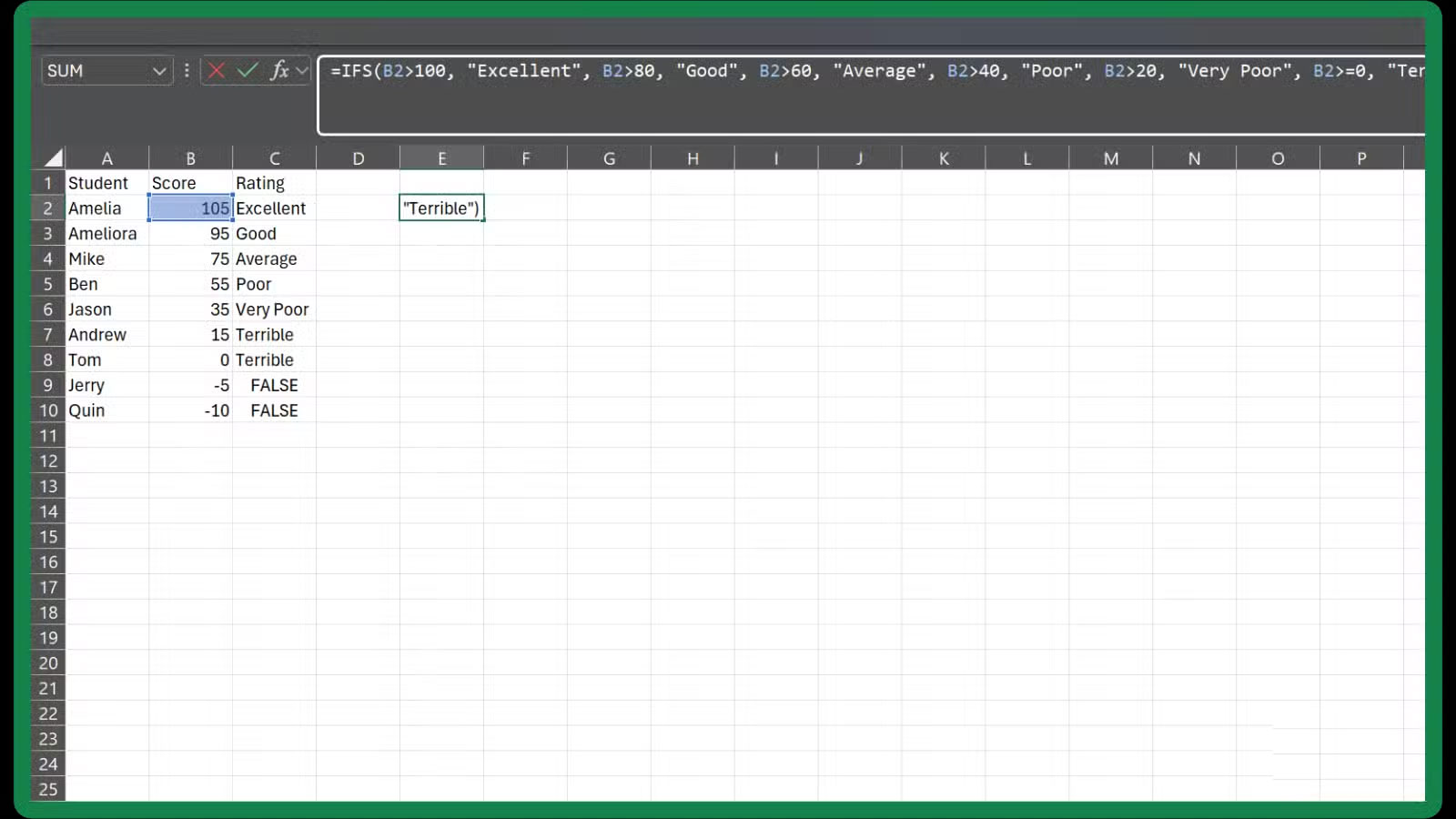

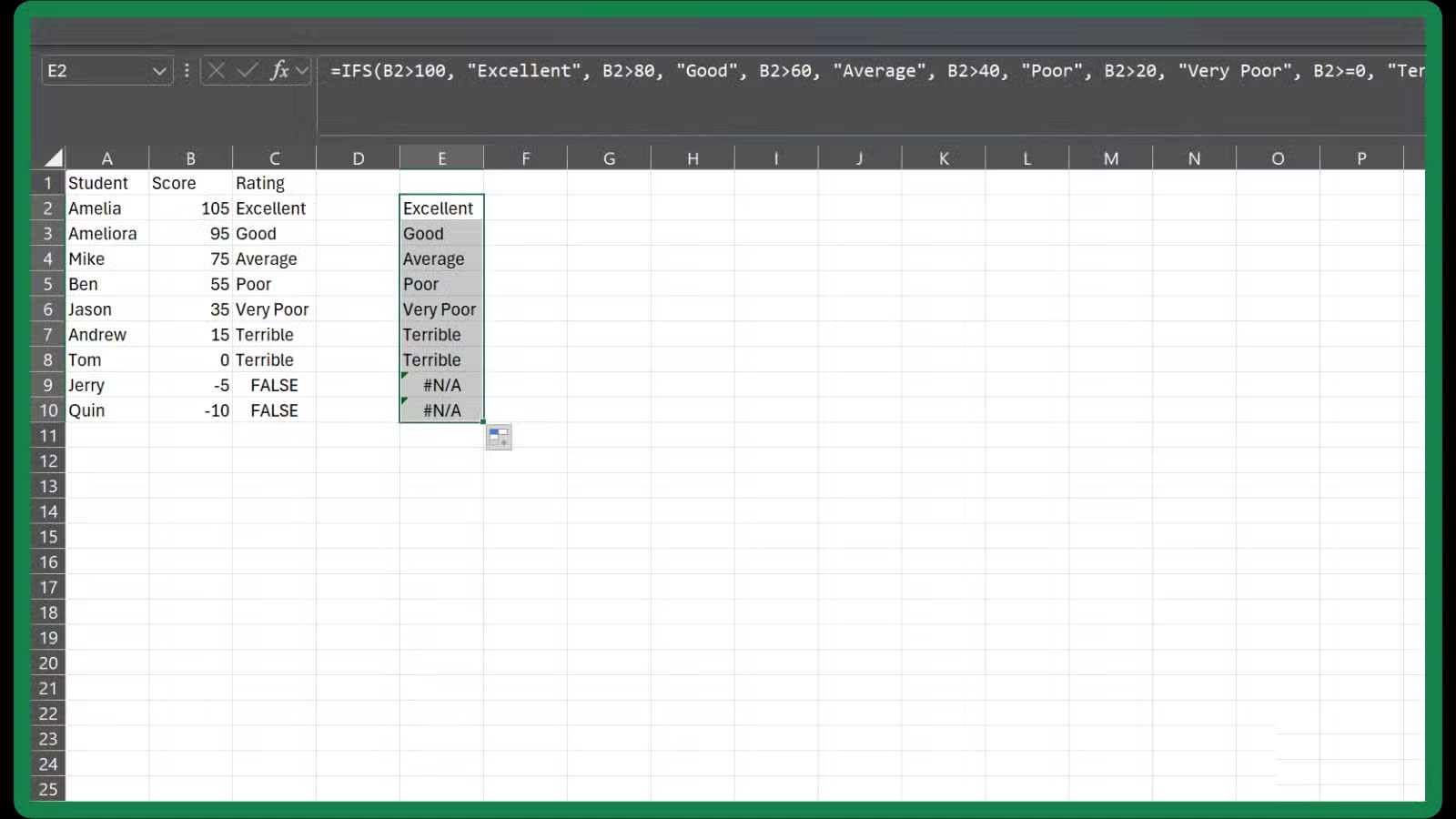

Fortunately, Microsoft introduced the IFS function to solve many of these problems. Available in Office 2019 and Microsoft 365 subscription plans, the IFS function can replace many nested IF statements in Excel and is much easier to read. Here is an example of a scoring formula using IFS:

=IFS(B2>100, "Excellent", B2>80, "Good", B2>60, "Average", B2>40, "Poor", B2>20, "Very Poor", B2>=0, "Terrible")The IFS function works by checking the conditions in order: test1 , value-if-true ; test2 , value-if-true ; and so on, for any number of tests (up to 127). In simple terms, you're saying: "If the score is above 100, it's Excellent; if it's above 80, it's Good; if it's above 60, it's Average.".

IFS is a huge step up from nested IF functions, but it's not perfect. You still have to repeat any complex calculations inside each condition. That's where LET comes in, and it turns IFS from good to great.

The LET function is a more concise way of writing complex logic.

The Secret to Writing Excel Formulas You Can Actually Maintain

With the LET function, you can name a complex calculation, perform it once, and then reference that name throughout the formula. This makes your logic much more efficient and easier to follow. Here's how LET can further simplify your scoring formula with the IFS function:

=LET(score,B2,IFS(score>100,"Excellent",score>80,"Good",score>60,"Average",score>40,"Poor",score>20,"Very Poor",score>=0, "Terrible"))The difference is clear, as you can immediately tell what the score means without having to dig through cell references. While this is a simple case, it's only a small part of what LET can do.

The LET function supports up to 126 variables, which means you can break down even the most complex logic into more manageable pieces. It also improves performance. Normally, if you repeat the same expression multiple times, Excel will recalculate each time. With LET, you calculate it once, name it, and reuse it as needed.

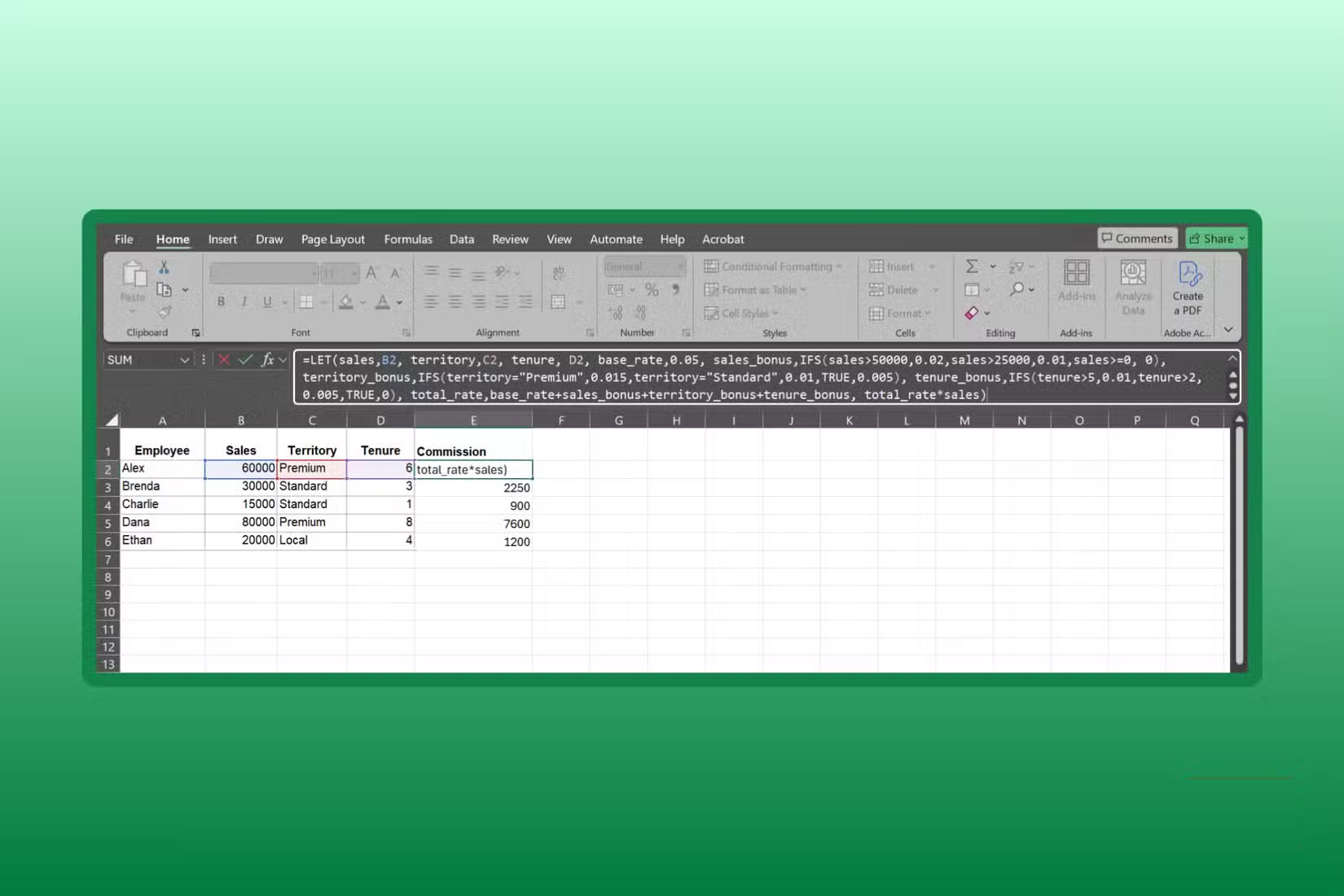

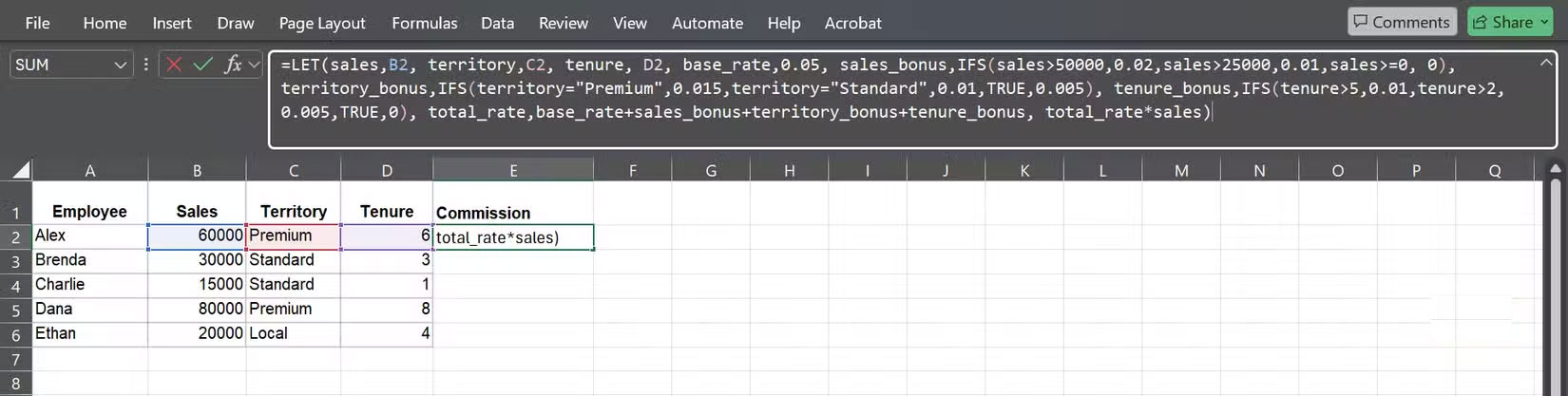

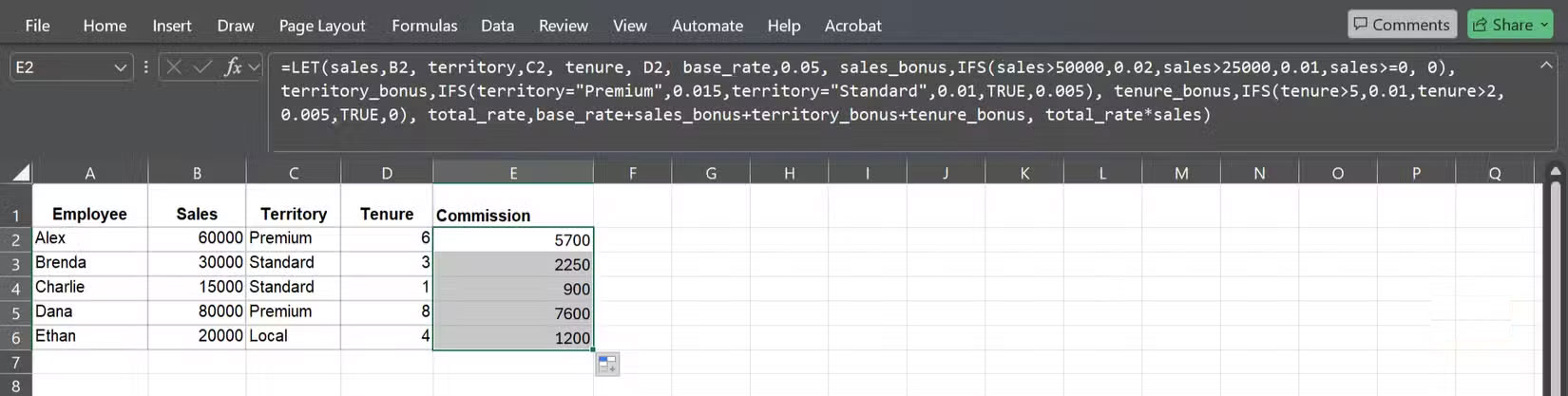

Here's a more complex example that shows the true power of combining LET and IFS. Imagine you're calculating commission rates based on sales performance, region, and time worked:

=LET(sales,B2, territory,C2, tenure, D2, base_rate,0.05, sales_bonus,IFS(sales>50000,0.02,sales>25000,0.01,sales>=0, 0), territory_bonus,IFS(territory="Premium",0.015,territory="Standard",0.01,TRUE,0.005), tenure_bonus,IFS(tenure>5,0.01,tenure>2,0.005,TRUE,0), total_rate,base_rate+sales_bonus+territory_bonus+tenure_bonus, total_rate*sales)This formula calculates an employee's total commission by combining base rate, sales bonus, regional bonus, and time bonus.

The general syntax for LET is LET(name1, value1, name2, value2, …, calculation) , and you can see that structure in action in this example. Each variable is defined at the top – sales, territory, tenure, base salary, and three bonuses – before being combined into the final total salary. Each part of the formula is labeled and easy to follow, rather than buried in a bunch of repetitive logic.

A formula like this would be incredibly difficult to write and maintain with nested IF functions. With LET and IFS, every element is clearly defined and easy to adjust. If you need to change the premium territory bonus, you only need to update one line. Without LET, you would have to search through the entire formula, find and fix each instance manually.

Ultimately, you'll have a recipe that's easier to maintain and less likely to break when you revisit it months later.