Korean scientists have just found a solution to the century-old physical barrier.

A joint research team from Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) and Jeonbuk National University has demonstrated that mechanical waves can be completely trapped in a single solid resonator. Previously, many scientists thought this was 'theoretically impossible' in compact systems. The research results, published on April 3 in the journal Physical Review Letters , focus on a phenomenon called 'bound states in the continuum' (BIC), where waves are trapped and do not lose energy, despite the presence of natural 'escape routes' in the environment.

Resonance is the principle at the heart of many familiar devices, from smartphones to ultrasound machines to radios. Resonators amplify waves at a specific frequency, but they tend to leak energy over time, requiring constant power. Nearly a century ago, John von Neumann and Eugene Wigner predicted that under special conditions, waves could be trapped forever without loss. These states are called BICs, but were long considered impossible in single systems.

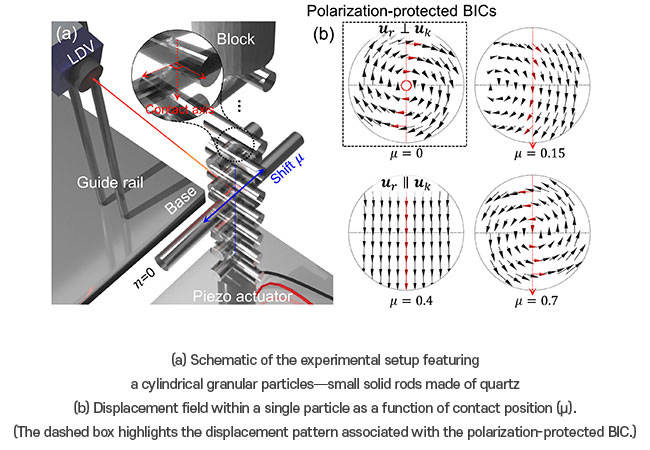

In the new study, the scientists not only provide a theoretical basis but also successfully demonstrate experimentally that BIC can indeed exist in compact solid-state resonators, protected by polarization. They fabricated a tunable mechanical system from cylindrical seed crystals made of quartz. The key lies in the contact surfaces between these cylinders: by simply adjusting those contacts, they can actively 'switch modes' between BIC and quasi-BIC.

In particular, when arranged in a certain configuration, the team observed a waveform that was completely trapped within a single cylinder without leaking into the surrounding areas. This was confirmed using a laser Doppler vibrometer, which showed a resonance quality (Q-factor) of over 1,000 – meaning the oscillations were virtually undamped and lost minimal energy.

When multiple individual resonators are linked together, these 'trapped' wave states can combine and form unique wave bands in a periodic structure. The team even created a series of pillars with a deliberate asymmetry, resulting in a flat band – where the group velocity of the wave is zero at a given frequency. This means that the energy 'stands still' rather than spreading out. All the pillars in the series exhibited stable resonances with high Q-factors and no dispersion.

' It's like throwing a stone into a still lake, but the ripples don't spread out, they just vibrate in place ,' explains lead author Dr Yeongtae Jang. ' The system allows the waves to move, but the energy is completely locked in place .'

The team calls this phenomenon at the chain level Bound Bands in the Continuum (BBIC) . According to them, this could be the basis for potential applications in energy harvesting, ultra-sensitive sensors, or communications technology, where energy storage and loss are key.

' We have broken a theoretical barrier that has existed for a century ,' stressed Professor Junsuk Rho, who led the research. ' Although the work is still at the basic research level, the practical implications are huge – from energy-saving devices to next-generation sensing and signal transmission technologies. '

In simple terms, the team created a system of quartz rods, in which the contact points act as 'ultra-precise tuning knobs'. When the 'knob' is turned correctly, a wave can be completely trapped within a single cylinder without loss. When multiple such cylinders are connected, the trapped oscillation can persist throughout the entire chain, remaining in place without spreading. This opens a clear path to studying and applying strong wave confinement in compact solid systems.

You should read it

- ★ Homemade keyboard is not difficult

- ★ 5 best mechanical keyboards for Mac in 2024

- ★ What file is WAV and WAVE? How to open, edit and convert WAV and WAVE files

- ★ See the strange mechanical keyboards of the Vietnam Mechanical Keyboard Association

- ★ What is a mechanical keyboard? Compare mechanical keyboards and regular keyboards