How can dead cells create 'footprints of death', helping viruses spread?

Even when they die, cells leave traces behind. Scientists have discovered a tiny 'footprint of death' that not only helps the immune system clean up, but could also create a new way for viruses to spread disease.

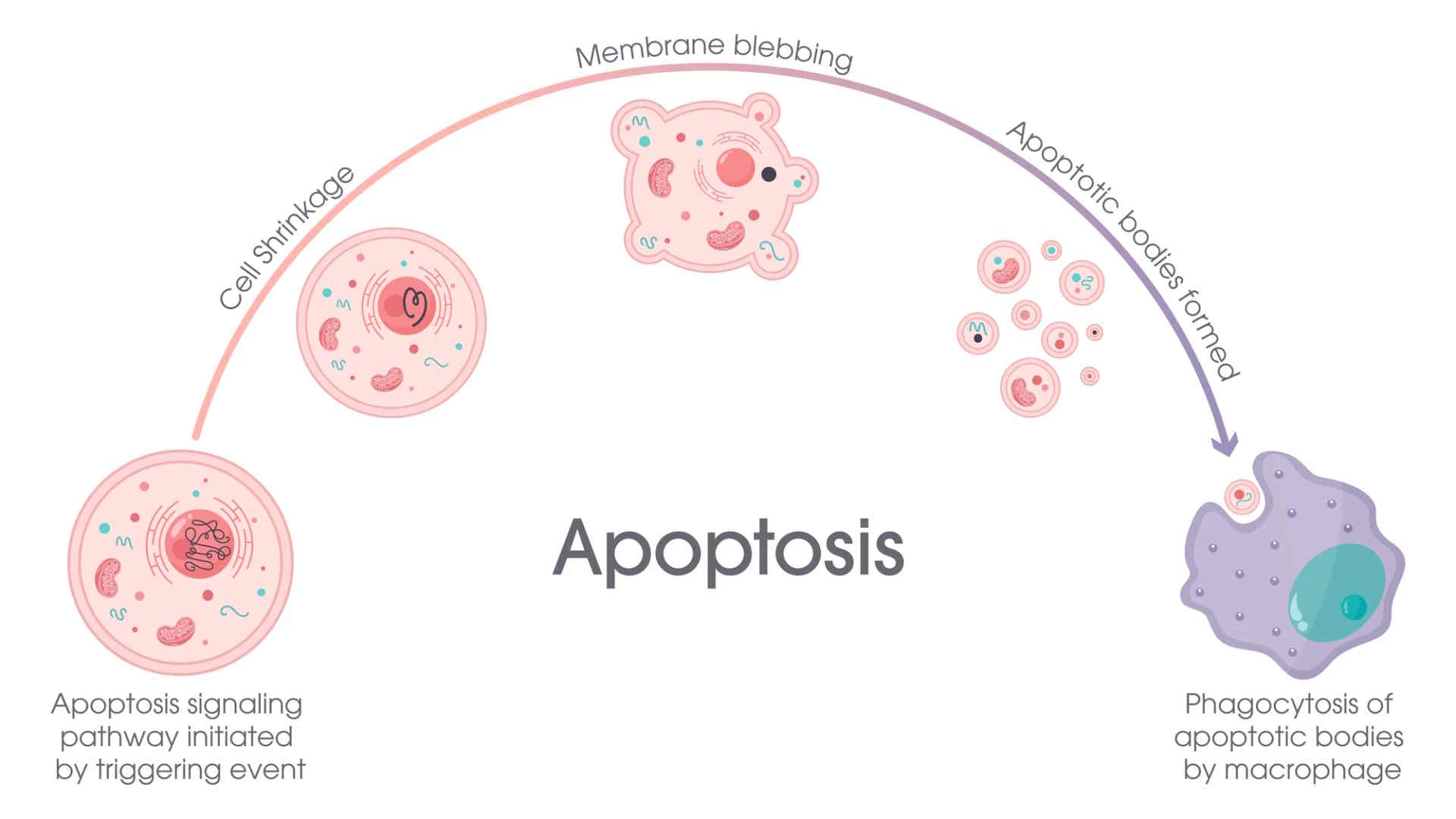

When cells die through apoptosis, a natural, programmed form of cell death, they send signals to nearby immune cells (phagocytes) to clean up the remains. Scientists already know about some of these traces, including 'find me' and 'eat me' signals, and small, bubble-like sacs released by dying cells, called apoptotic extracellular vesicles (ApoEVs).

However, a new study led by La Trobe University has identified a physical footprint left by dead cells that clings to surfaces and can help guide phagocytes to the right place to die. These footprints have been dubbed 'Footprints of Death', or more simply, FOOD.

' Understanding this fundamental biological process could open up new avenues of research to develop new treatments that exploit these steps and help the immune system fight disease better ,' said study co-author Professor Ivan Poon, PhD, lab head at the La Trobe Institute for Molecular Sciences (LIMS). ' Billions of cells are programmed to die every day as part of normal metabolism and disease progression, and until now, it was believed that the process of cell fragmentation during cell death was random and fairly simple. '

The team used microscopy, live-cell imaging, proteomics and viral infection models to study how FOOD forms and functions. Some of the methods included stimulating human and mouse cells to undergo apoptosis, using advanced microscopy to record how cells shrink during death and leave behind 'footprints', and the proteins found in the FOOD structure to better understand its composition and role.

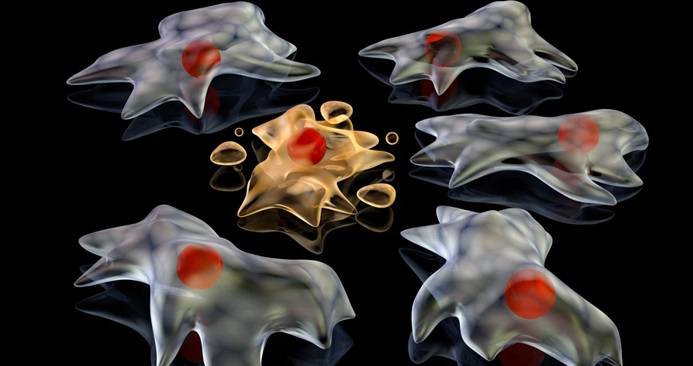

They found that when cells adhered to a surface die, they retract their cell bodies and leave behind a thin, membrane-bound footprint that remains firmly attached to the surface. These footprints are rich in F-actin, a structural protein, and other adhesion proteins. They are anchored to the underlying surface, unlike most floating extracellular vesicles. FOOD appears in almost all cell types tested and under a variety of lethal agents.

After a cell leaves its footprint, the remaining membrane gradually rounds into vesicles about 2 µm wide called FOOD-derived extracellular vesicles (F-ApoEVs). These vesicles trigger the classic 'eat me' signal, telling immune cells to engulf them. This process depends on the activation of ROCK1, a protein that regulates cell contractility. When ROCK1 is disabled, FOOD fails to form properly. Proteomic analysis found 601 proteins in FOOD, including proteins involved in cell structure and adhesion (actin, tubulin, vinculin, and integrin). There was very little nuclear or mitochondrial material, suggesting that FOOD mainly consists of membrane components and the cytoskeleton.

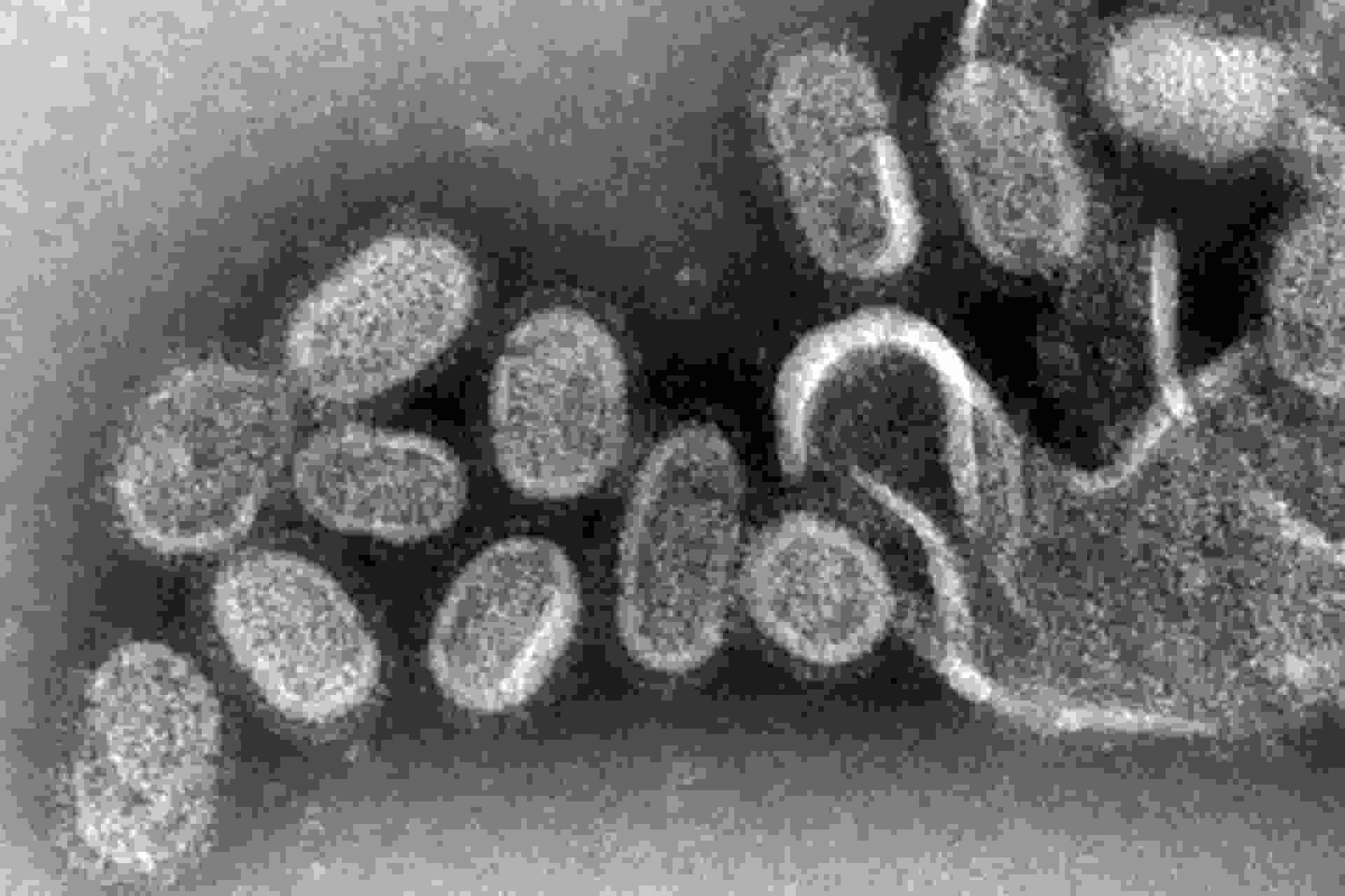

When immune cells (macrophages) are placed near FOOD, they recognize and engulf the F-ApoEVs, which then locate the dead cell. Macrophages exposed to FOOD become more efficient at clearing other dead cells afterward, suggesting that FOOD has 'primed' them for cleanup work. In influenza A- infected cells , FOOD and F-ApoEVs contain viral proteins and even intact virions, which are complete, infectious virus particles that exist outside the host cell. When these infected vesicles mix with healthy cells, they spread the virus, suggesting that FOOD can act as a virus reservoir. This means that the process that helps the immune system locate dead cells can also be hijacked by viruses to infect new cells in some cases.

' We know that the body removes dead cell fragments to prevent them from persisting and causing inflammation and autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and we found that F-ApoEVs were easily removed from the site of cell death ,' said lead author, PhD student Stephanie Rutter, a senior researcher in Poon's LIMS lab. ' What we didn't expect was that viruses could also take advantage of this process and cause infection by hiding in F-ApoEVs. '

' This study has revealed that dead cells can continue to communicate from within the body and can influence immune function ,' added the study's other author, Dr. Georgia Atkin-Smith, a senior postdoctoral researcher at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI).

However, this research has limitations. It was primarily performed in vitro (in cell cultures), so it is unclear how FOOD functions inside living organisms. FOOD formation is primarily observed in adherent cells, so its role in free-floating (i.e., non-adherent) cells, such as blood cells, may be different. The long-term fate of FOOD structures in tissues, such as whether they persist or degrade, is unknown. Finally, the findings on viral spread are specific to influenza A; other viruses may behave differently.

However, FOOD may explain how some viruses persist and spread in tissues even after infected cells die. Because FOOD helps macrophages seek out and remove dead cells, it may suggest new strategies to promote tissue repair or control inflammation. Further research into FOOD could lead to more precise therapies that modulate immune responses.

' The more we understand about cell death and what happens to cells after they die, the better we can understand diseases and find new treatments ,' says Rutter.

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.