A forgotten feature of Windows Phone that even modern phones can't match.

It's been a decade since Microsoft officially admitted defeat in the smartphone war, but the ghost of Windows Phone continues to haunt the industry. Parts of the operating system still survive in the form of apps that bring the Live Tile interface to Android and launchers that maintain the OS's bold Metro design language – something neither Android nor iOS has been able to match to this day.

But there's one specific feature that no other phone manufacturer is currently considering implementing. It's not a piece of hardware or a smooth operating system animation. It's People Hub. In 2025, your phone will essentially be just a launcher for individual apps. Windows Phone has a different idea: Phones should focus on people, not apps.

Windows Phone's People Hub philosophy

Microsoft's tile-first design has unified apps, people, and content in a way that iOS and Android have yet to replicate.

To understand why People Hub is so revolutionary, you need to recall the technological landscape of 2010. The iPhone had just established the grid-based icon model, a model we largely still follow today. If you wanted to see what your best friend was up to, you opened Instagram. To read their thoughts, you opened X or Threads. To message them, you opened WhatsApp or Messenger. You were switching between "fenced gardens" fragmented by corporate interests.

It's unclear whether Microsoft anticipated this, but the person in charge of Windows Phone looked at the icon grid and realized a problem: It forced you to do everything yourself.

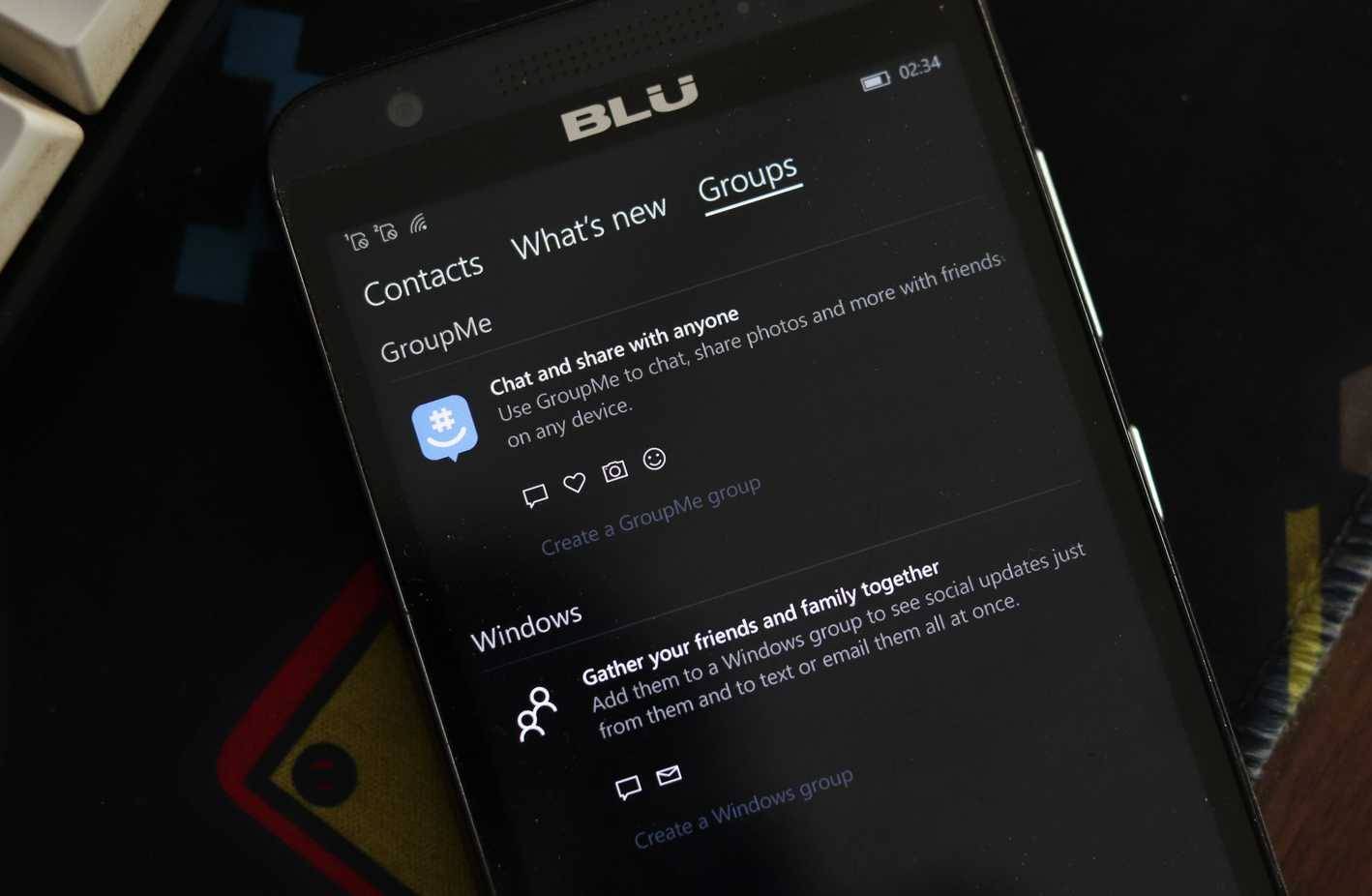

The solution Windows Phone offers is "Hubs". Instead of 50 different apps, the operating system has grouped content into panoramic views. You have the Music + Video Hub, the Pictures Hub, and the crown jewel, the People Hub.

People Hub is more than just a contact list. It's a dynamic social media dashboard . When you tap on a contact, you see not just their phone number and email address. You see their latest Twitter post, most recent Facebook photo, LinkedIn status, and Windows Live updates, all gathered together in a sleek, horizontally scrolling text interface.

The integration happens in both directions. Windows Phone also includes a "Me" tile that acts as a centralized control panel for your own digital identity.

If you want to post an update, you don't need to search for a specific social media app. Tap the "Me" tile, enter your status, and select the tiles for the social media platforms you want to post to. With just one tap, the post will go viral across all your social media platforms.

This might sound trivial today, but the feeling of using it was very different. You weren't using Facebook or Twitter (now X), you were simply communicating. The operating system abstracted the service layer, treating social networks as utilities rather than destinations. It felt like you were in control of your digital life, not a passive consumer of algorithms displaying information.

Perhaps the most useful aspect of this integration is the consolidation of messaging apps. If you're texting someone and they're offline, the phone can transfer the conversation to Facebook Chat without interrupting the flow of the conversation. There's no need to install a separate Facebook Messenger app. All messages are treated as text messages.

This is something Android has desperately tried to replicate with RCS and Google Messages, and something Apple is holding onto with iMessage. But even those implementations are limited by their specific protocols. Windows Phone doesn't care about protocols; it only cares about who you want to talk to.

Why can't modern phones compete?

The limitations of current standalone application systems are worse than you might think.

So why does People Hub no longer exist? Why can't the iPhone 17 or Pixel 10 automatically retrieve your friends' latest posts or Instagram stories to your contacts?

The answer is the same as the reason for Windows Phone's failure: this feature was far ahead of its time.

People Hub worked effectively because, in the early 2010s, social networks had open APIs. They were eager to grow and willing to let Microsoft collect their data to display on the Windows Phone user interface. But as the decade passed, the business model of the internet changed.

Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram realize that if you view their content within Microsoft's People Hub, they can't show you ads. They can't track your online time. They can't pull you into an algorithmically designed "For You" feed that makes you scroll for hours on end.

People Hub was incredibly efficient. It allowed you to just glance and leave, a stark contrast to the pointless "scrolling" interaction metrics that modern tech giants crave. APIs were shut down one by one. Social media giants forced Microsoft to remove integrations, requiring users to open a standalone application. People Hub's stunning panoramic views gradually turned into ghost towns, eventually leaving only simple deep links.

The user experience we lost along the way.

Today's devices seem more powerful but are less connected.

Today, we have better screens, faster processors, and more powerful cameras than Lumia engineers ever dreamed of. However, the user experience in managing relationships and using the phone has regressed. Many people will still use Windows Phone in 2025 if they can.

On a modern phone, social media means managing dozens of different apps. It means remembering where a conversation is taking place, being bombarded with ads and algorithmic suggestions every time you want to see a photo your friends have posted. And if you combine it all, you have AI features that can annoyingly intrude on your private messages, emails, and photos.

We traded a user-centric interface for an advertiser-centric interface.

Windows Phone had many shortcomings. It lacked apps, launched late, and the reboot from Windows Phone 7 to 8 disappointed early users. But its vision of a human-centered operating system offered a glimpse into a more humane digital future. It treated your contacts as people, not content creators, and it treated you as a person, not a collection of eyes serving to add ads.

It's a forgotten feature that modern smartphones will probably never match. It's not about programming code, it's about respect. And it's not something that the big software or technology companies of today want to revive.