Here's how solar storms help develop life on alien planets

Solar storms don't just bring destruction, they also bring the chance of life on alien planets. That's the latest announcement from scientists' research.

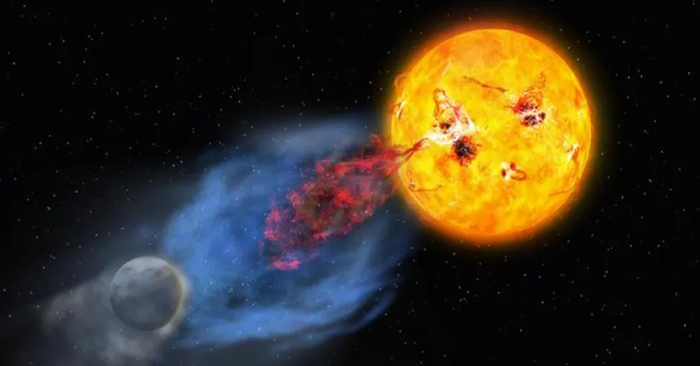

For the first time, we have seen an entire coronal mass ejection on another star. This suggests that when these violent outbursts occur on young stars, they contain enough energy to potentially kick-start the chemistry of life on any orbiting planet.

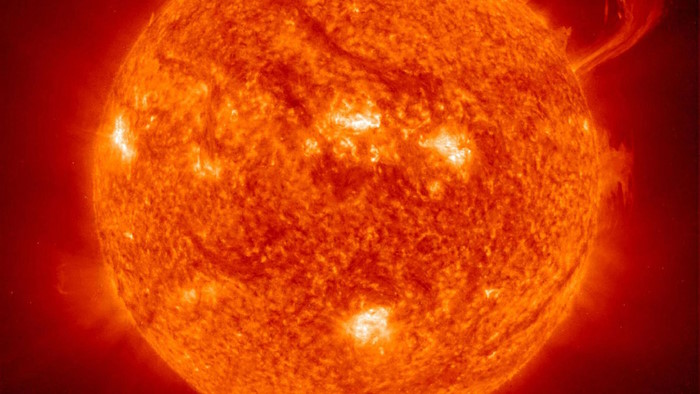

Young stars can be much more turbulent than older ones. Stellar physics predicts that in the Sun's formative years, it emitted radiation bursts and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that were much more powerful and frequent than what the Sun can handle today.

However, no one has actually seen a young Sun-like star that is so energetic — until now.

Coronal mass ejections and associated flares occur when the magnetic field lines on the Sun or another star are disrupted, releasing a huge burst of energy before they reconnect. This energy manifests as a brightening of the surface of the Sun or star, and can also lift a huge jet of plasma directly from the corona, the extremely hot outer layer of a star's atmosphere.

We're used to seeing CMEs on the Sun, but extraterrestrial CMEs are harder to spot. However, ground-based telescopes observing at hydrogen-alpha wavelengths have detected cold, lower-energy plasma escaping young stars in CMEs. The next step is to look for the higher-energy release that stellar physicists believe is characteristic of regular CMEs from young stars.

To that end, a multinational team of astronomers led by Kosuke Namekata of Kyoto University in Japan has made a breakthrough by targeting the young Sun-like star EK Draconis, located 112 light-years from Earth in the constellation Draco (the Long). The star is thought to be between 50 million and 125 million years old, which is considered very young for a star that will last for billions of years, and has a mass (0.95 times the mass of the Sun), radius (0.94 times the radius of the Sun) and surface temperature (5,560 to 5,700 degrees Kelvin) very close to those of the Sun.

" What inspired us most was the long-standing mystery of how the young Sun's violent activity affected the early Earth, " Namekata said in a statement. " By combining space-based and ground-based facilities across Japan, Korea, and the United States, we were able to reconstruct what may have happened billions of years ago in our solar system ."

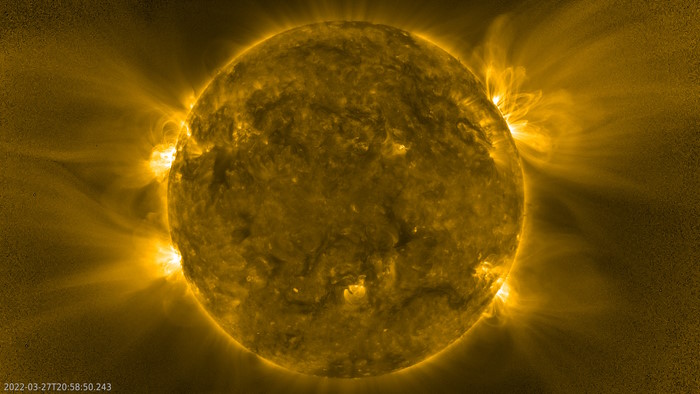

Namekata's team made simultaneous observations of EK Draconis using the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and three ground-based telescopes in Japan and South Korea. The Hubble observations were made using ultraviolet light, allowing them to detect the higher-energy components of a CME, while the ground-based telescopes monitored the cooler plasma through its hydrogen-alpha emission, and TESS observed the brightening caused by the accompanying flare.

Hubble and ground-based telescopes together detected spectral lines from the emission of a CME on EK Draconis. Hubble's ultraviolet vision detected a cloud of hot plasma with a temperature of 100,000 Kelvin (180,000 degrees Fahrenheit). The Doppler shift in the ultraviolet spectral lines from the star suggests that the hot plasma was ejected at velocities ranging from 300 to 550 kilometers per second (670,000 to 1.2 million miles per hour). Ten minutes later, a cooler stream of gas with a temperature of 10,000 Kelvin (18,000 degrees Fahrenheit) appeared, moving more slowly at 70 kilometers per second (157,000 miles per hour). Both the hot and fast components and the cold and slow components are two sides of the same CME.

This regular release of energy is large enough to drive chemical reactions in a planet's atmosphere, creating greenhouse gases that could keep the planet warm, as well as breaking down atmospheric molecules so they could reform into complex organic molecules, potentially serving as the basis of life, the researchers say.

These observations therefore provide a rare insight into the role each star played in the origin of life, a role our Sun may have played 4.5 billion years ago and that other stars may be playing today.

The findings were published October 27 in the journal Nature Astronomy.