'Erosion of trust': Social media's a mess amid George Floyd protests

Bouquets of brightly colored flowers and prayer candles rest at the door of a small windowed guard booth in downtown Oakland, California. A ribbon with an American flag motif waves from the door handle. Two bullet holes pockmark the booth's windows.

This is where Dave Patrick Underwood, 53, was fatally shot around 9:45 p.m. on Friday while working as contract security officer for the Department of Homeland Security, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The shooting, which also seriously injured another DHS contract security guard, took place a few blocks from where thousands of protestors had gathered to protest the killing of George Floyd. The 46-year-old unarmed black man died after a white police officer jammed a knee onto his neck for nearly 9 minutes. The officer has been charged with murder. Like Floyd, Underwood was African American.

Initial news reports of Underwood's shooting linked the incident to the protests. As is often the case, the conjecture on Twitter and other social media sites ran away from the changing facts on the ground. As early as Friday night, the Oakland Police Department sent an alert to reporters saying the shooting didn't appear to be related to that night's demonstrations. And the FBI has never linked the two in its statements to the press. It confirmed to CNET that Underwood died in a drive-by shooting but declined to comment further because its investigation is ongoing.

For Twitter, the FBI's report appeared to be too late. Hashtags like #PatrickUnderwood and #JusticeForPatrickUnderwood had already started trending, buoyed by accounts that declared Underwood was "murdered" by protesters and "rioters." The association with Oakland's protesters, true or not, had already spread -- going as far as the White House.

Misinformation on social media is nothing new. Russian agents tried to sway the 2016 US presidential election with divisive tweets and Facebook posts. Message board chatter about "Pizzagate," a conspiracy theory that falsely accused Hillary Clinton and others of operating a child sex ring out of a restaurant, led to gunfire in Washington, D.C. Hoaxes, often disguised as legitimate news, have spread far and fast, thanks to social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, as well as 4chan, 8kun and other anonymous message boards.

But social media's inability to contain the explosion of misinformation takes on new urgency as peaceful protestors battle the perception that all of the demonstrations have devolved into looting and violence. Twitter's role in spreading news in real time without any checks makes it particularly vulnerable to manipulation. Over the past few days, along with tweets about protestors being responsible for Underwood's death, other false theories have made the rounds, including an internet blackout in Washington, D.C. and the far-left militant group antifa sending protesters to cause unrest in cities across the US. And once something hits Facebook, with its over 2.6 billion monthly active users, it's hard to counteract.

"It's very important for both of these platforms to get it right, not just one or the other," said Jennifer Grygiel, an assistant professor of communications at Syracuse University. "We need both."

In a speech on Monday, President Donald Trump said the nation "has been gripped by professional anarchists, violent mobs, arsonists, looters, criminals, rioters, antifa and others," painting a grim picture of the mostly peaceful protests that have swelled to more than 140 cities across the country. Trump brought up Underwood.

"A federal officer in California, an African American enforcement hero, was shot and killed," he said. "These are not acts of peaceful protest. These are acts of domestic terror."

Even as misinformation has flourished on social media, allowing critics of the protests to craft their own narrative of the demonstrations, the platforms continue to serve another purpose. Organizers also have relied on the sites -- especially Twitter -- to coordinate demonstrations and share important updates on the ground. Journalists use it to report developments, and citizens follow along to learn what's happening in their cities. But some people have taken advantage of the widespread use of social media to sow confusion among the protestors.

Twitter says it's trying to address this problem.

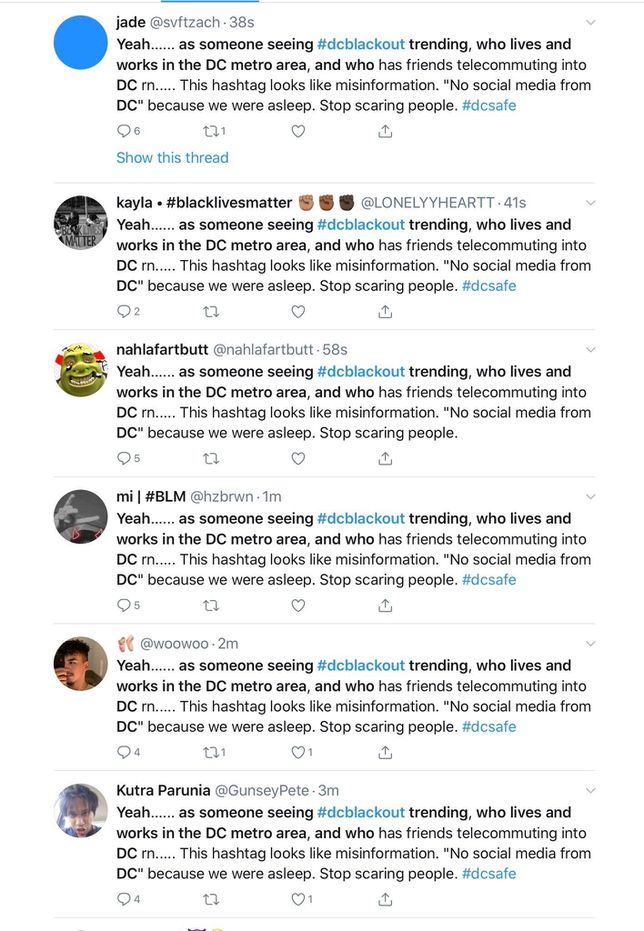

"We're taking action proactively on any coordinated attempts to disrupt the public conversation around this issue," a Twitter spokeswoman said. "For example, we are actively investigating the hashtag #dcblackout and during this process have already suspended hundreds of spammy accounts that Tweeted using the hashtag."

The spokeswoman also said Twitter "may" prevent certain content -- like topics that incite hate on the basis of race -- from trending.

"There is such an erosion of trust that we have really decimated this platform that is super valuable for organizing."Facebook, for its part, said in a statement that its teams "have been working to find and remove violating activity since the protests started. We're using automated detection systems, fact-checking, reducing content distribution and removing content that violates our policies."

Facebook pays an army of fact-checkers to verify potentially problematic posts, but Twitter doesn't have that sort of manpower. It tends to lean on machines, though humans step in for big decisions. And while it will sometimes slap a warning label on a tweet, as it recently did to several posts from Trump, lots of misinformation simply flows through the site untouched.

"It doesn't really matter who or where it's coming from," said Maddy Webb, an investigative researcher at First Draft, an organization that tracks and combats online misinformation. "There is such an erosion of trust that we have really decimated this platform that is super valuable for organizing."

Misinformation's spread

Early Monday morning, the hashtag #DCblackout had begun circulating throughout Twitter. It referenced a fake story that said no social media would be accessible in the city due to the civil unrest. As the hashtag spread, the claims behind it became wilder -- that phones and other means of communication were being blocked and police were replacing rubber bullets with gunpowder ones.

By Monday afternoon, the hashtag had nearly 1 million mentions, according to NPR.

Netblocks, a group that tracks internet disruptions and shutdowns, followed the tweets about the #DCblackout and monitored network traffic in real time. It never saw instability in the connections, indicating the rumor wasn't true.

"Fact check," NetBlocks tweeted on Monday. "Washington, D.C. did not have a city-wide blackout."

In a fast-paced, constantly evolving environment, like the protests around Floyd's death, false information can overwhelm Twitter. On Sunday alone, Black Lives Matter, Floyd and the protests about his death were mentioned 21.2 million times across all forms of media, including Twitter, according to Zignal Labs. Since May 25, there have been over 101 million mentions, the media intelligence company said. Some of that information is being weaponized to fit people's political agendas.

One hoax spreading widely is that antifa is behind the country's more violent protests and that it has been busing protesters into predominantly white areas of cities to loot homes and businesses.

Kathleen Carley, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, said a study of tweets around the protests show that essentially no humans have been using the antifa hashtag. Instead it's largely bots, according to the data crunched by Carley and her team from May 25 through Sunday. She estimates that 30% to 49% of users posting about the protests likely are machines, not humans. It doesn't mean all of them are posting inaccurate information, but they're helping sow confusion, she said. (Twitter hasn't said how many bots are involved in recent tweets, but some social media experts have disputed the tallies.)

"Disinformation is really hard to discern."Just shutting down all bots isn't the answer, she said. Many spread helpful news, like earthquake alerts.

"Disinformation is really hard to discern sometimes," Carley said. "Based on the hashtags, [bots are] more [often] making the protests a political issue about things other than Black Lives Matter or other than George Floyd."

While Trump hasn't been using antifa hashtags, he has been tweeting about the activists, labeling them a terrorist organization and blaming them for the country's protests. Over the past week, people posted similar sentiments on Facebook more than 6,000 times, according to The New York Times. And those posts tallied more than 1.3 million likes and shares, the paper said Monday.

The widespread scrutiny and chaos on social media is causing both Twitter and Facebook to react.

Social media's response

Last week, Twitter did something never before seen on its site: It put a label on two tweets from President Trump, warning they contained "potentially misleading information about voting processes." A couple of days later, Twitter also hid an overnight tweet from Trump behind a label, saying it violated the company's rules about "glorifying violence."

"When the looting starts, the shooting starts," Trump had tweeted, using a phrase from a Miami police chief in the 1960s that's widely seen as a violent threat against protesters.

Facebook, meanwhile, took a more hands-off approach. The social networking giant, which makes a lot of money from political ads (something Twitter bans on its site), left up a similar post from Trump. In response, Facebook employees staged a rare protest, and several said they were quitting working for the company. Online therapy company Talkspace also ended its partnership discussion with Facebook because the startup "will not support a platform that incites violence, racism and lies," in the words of its founder Oren Frank.

For his part, Trump struck back. On Thursday, he signed an executive order that called for a reinterpretation of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. The law, which ensures free speech on tech platforms, designates online companies such as Facebook and Twitter as "distributors" rather than "publishers" of content. That prevents them from being sued for every negative review or comment posted on their sites. Many experts say Trump's order is largely symbolic and unenforceable, however.

"When Section 230 was crafted, no one thought about having to try to moderate the president of the United States," Syracuse's Grygiel said. "They're still grappling with this."

Typically, fact checkers call on social media to take a few steps when it comes to combating misinformation. They suggest moderating the content, as well as getting rid of the retweet and share buttons, which would make it harder to disseminate fake information quickly.

In the case of the protests, those strategies likely won't work, says First Draft's Webb. While retweeting and sharing information can spread misinformation quickly, those tools also are vital for protestors to coordinate. And there's too much information flowing during protests for the social media sites to moderate them without hurting free speech and potentially labeling accurate information as false. Setting fair removal policies could be tricky, she said.

"We know that those kinds of policies target people who already don't have a lot of opportunity to speak," Webb said.

If Twitter and Facebook can't find ways to scrutinize themselves, it may be up to their users to be more careful about what information they share and believe. That means doing things like reverse image searches and waiting before immediately retweeting something, she added. And eventually, the companies could face more government regulation.

As Twitter tries to walk the line between allowing free speech and curbing misinformation, Underwood's name is still being used as a way to capture a narrative. Meanwhile, his friends and family are trying to remember the man who lost his life on Friday night.

The federal building where Underwood worked is still cordoned off with police tape. On the makeshift memorial at the guard booth where he died is a piece of paper with his picture and a link to a GoFundMe site for donations for his family. Underwood's sister and a cousin didn't respond to requests for comment.

"Two of our Federal Contract Officers were ambushed in an act of violent cowardice," Jennifer Tong, the supervisor for Underwood and his colleague, wrote on the fundraising site. "I have worked side by side with both men and cannot describe the pain we as their brothers in arms feel."