Blue laser solves 150-year-old physics mystery

For more than a century, physicists have known that a strange magnetic signal exists in common metals like copper and gold, but they have been unable to observe it. Now, using only a blue laser and a clever tweak in processing techniques, scientists have discovered this elusive phenomenon, called the optical Hall effect.

This breakthrough not only reveals hidden magnetic behaviors in materials once considered magnetically 'silent,' but also opens up new horizons in spin physics, quantum technology, and electronic design—without the need for wires or extreme conditions.

Light reveals hidden signals

An international team of researchers has found a groundbreaking way to detect tiny magnetic signals in common metals like copper, gold and aluminum using only light and a finely tuned optical technique. The discovery could lead to major advances in technology, from smartphones to quantum computers.

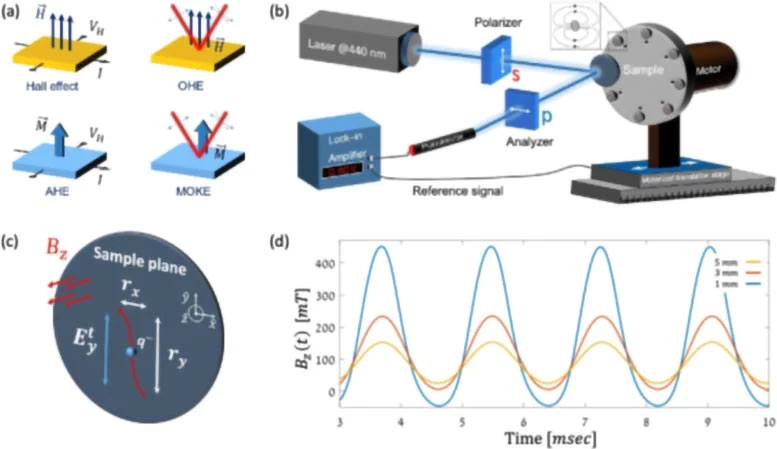

In theory, an electric current is deflected when exposed to a magnetic field. This phenomenon is called the Hall effect, and is well documented in magnetic materials such as iron. However, in some naturally non-magnetic metals such as copper and gold, the effect is much weaker and harder to observe.

A similar but lesser-known phenomenon, called the optical Hall effect, is thought to hold important information about how electrons move when subjected to both light and magnetic fields. Although understood theoretically for more than a century, the effect is too subtle to be detected with visible light. Experts believe it exists, but no one has yet developed a method sensitive enough to confirm it.

The research, led by Dr. Nadav Am Shalom and Professor Amir Capua from the Institute of Electrical Engineering and Applied Physics at the Hebrew University (Israel), in collaboration with Professor Binghai Yan from the Weizmann Institute of Science, Pennsylvania State University, and Professor Igor Rozhansky from the University of Manchester (UK), focuses on a difficult challenge in physics: how to detect tiny magnetic effects in non-magnetic materials.

'You might think of metals like copper and gold as magnetically 'silent . ' But in fact, under the right conditions, they still respond to magnetic fields—just in an extremely subtle way,' explains Professor Capua.

The challenge is to detect these small effects, especially when using light in the visible spectrum, where laser sources are readily available. Until now, the signal has been too weak to observe.

To solve the problem, the researchers advanced a method called the magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE), which uses lasers to measure how magnetism changes the reflection of light. Think of it like using a powerful flashlight to catch the faintest glimmer from a surface in the dark.

By combining a 440-nanometer blue laser with a large amplitude modulation of an external magnetic field, they dramatically increased the sensitivity of the technique. As a result, they were able to pick up magnetic 'echoes' in non-magnetic metals such as copper, gold, aluminum, tantalum, and platinum—a feat previously considered nearly impossible.

The Hall effect is an important tool in the semiconductor industry and atomic-scale materials research: it helps scientists determine the number of electrons in a metal. But in the past, measuring the Hall effect required attaching tiny wires to devices, a time-consuming and complicated process, especially when working with nanometer-sized components. The new method is much simpler: just shine a laser on the electronic device, no wires required.

Digging deeper, the team discovered that what appeared to be random 'noise' in the signal was not random at all. Instead, it followed a well-defined pattern related to a quantum property called spin-orbit interactions, which connect the way electrons move with the way they spin—a behavior that is important in modern physics.

This relationship also affects how magnetic energy is dissipated in the material. This understanding has direct implications for the design of magnetic memories, spintronic devices, and even quantum systems.

A new door into the world of spin and magnetism

The technique offers a non-invasive, extremely sensitive tool for exploring magnetism in metals, without the need for giant magnets or low-temperature conditions. Its simplicity and precision could help engineers build faster processors, more energy-efficient systems, and sensors with unprecedented precision.

'This research turns a nearly 150-year-old scientific problem into a new opportunity,' said Professor Capua.

Interestingly, even Edwin Hall, one of the greatest scientists who discovered the Hall effect, once tried to measure his effect with a beam of light but failed.