Rare discovery: A giant planet is forming in a cosmic dust vortex

A seemingly quiet star has just revealed one of the universe's biggest secrets: a giant gas planet forming in its own dusty disk.

For years, the star MP Mus appeared unremarkable—no planets, no gaps, no unusual activity. But when scientists analyzed images from the ALMA telescope more closely, combined with data from the Gaia satellite's stellar oscillation data, a dramatic picture emerged: a planet 10 times the size of Jupiter hiding in plain sight. It was the first time a planet had been discovered in this way, and it's likely that many more young, camouflaged planets are lurking in the dust clouds around other stars that we haven't yet seen.

The Hidden Giant

Astronomers have discovered a giant planet, estimated to be three to 10 times the size of Jupiter, hidden in a dense disk of gas and dust surrounding a young star.

The star, called MP Mus, was previously thought to be solitary, with no signs of orbiting planets. Previous observations had shown only a smooth, uniform cloud surrounding it.

But new data paints a different picture. Using detailed observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), along with measurements from the European Space Agency's Gaia mission, scientists have found evidence of a giant planet orbiting the star.

Led by a researcher at the University of Cambridge, the international team discovered a gas giant located in what is known as a protoplanetary disc – a flat, rotating ring of gas, ice and dust where new planets begin to form. This is the first time that data from Gaia has been used to identify a planet inside such a disc. The discovery points to a promising new method for finding young planets in the process of forming.

Planet formation in protoplanetary disks

Studying planet formation within protoplanetary disks helps scientists better understand how our Solar System came to be. In a process called core accretion, small particles are pulled together by gravity, gradually forming larger objects such as asteroids and planets. As the new planets grow, they disturb the surrounding disk, creating distinct gaps — similar to the grooves on a vinyl record.

However, observing these young planets is extremely difficult due to the intervening gas and dust in the disk. To date, there have been only three solid detections of young planets in protoplanetary disks.

" We initially observed this star knowing that most disks have rings and gaps. I was hoping to find features around MP Mus that suggested the presence of one or more planets ," said Dr Álvaro Ribas from the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy, who led the study.

Unusual "boring" disc raises questions

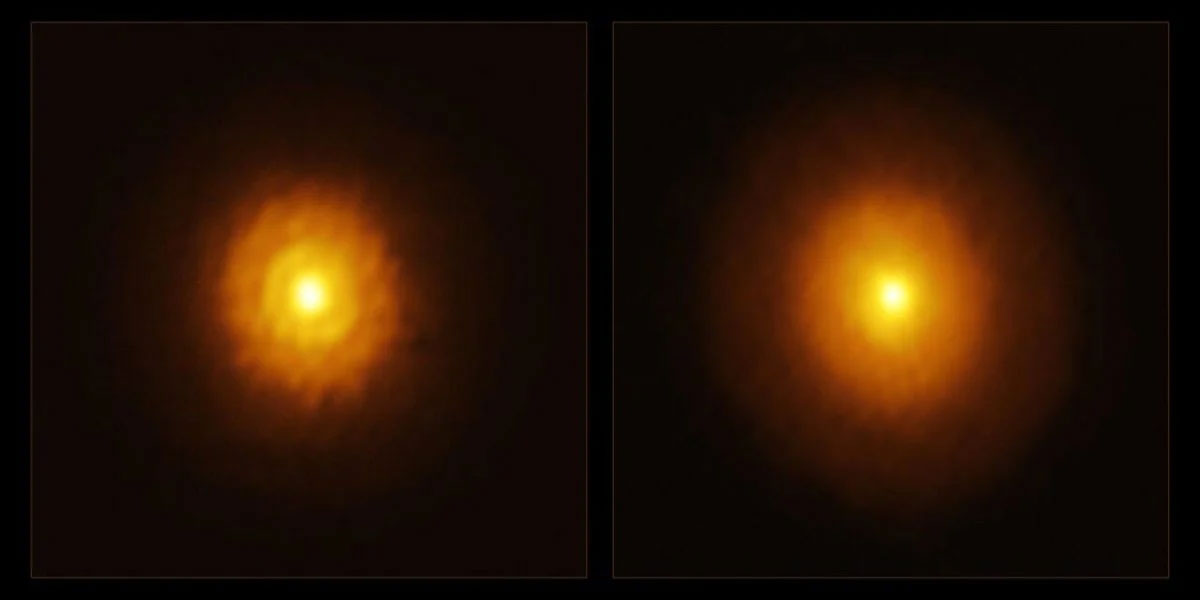

Dr. Ribas used the ALMA system to observe the protoplanetary disk around MP Mus (PDS 66) in 2023. The results showed a young star that appeared to be alone in the universe. The surrounding disk had no gaps that would indicate planetary formation, and was completely flat and featureless.

' Previous observations showed a flat, boring disk ,' Ribas said. ' But this seemed strange to us because the disk is 7-10 million years old. At that age, we would expect to see evidence of planet formation .'

Now, Ribas and colleagues from Germany, Chile, and France have revisited MP Mus. Using ALMA again, they observed the star at a wavelength of 3mm – longer than previous observations – allowing them to probe deeper into the disk.

New observations reveal a cavity near the star and two more distant openings — which were hidden in previous observations — suggesting that MP Mus may not be alone.

Meanwhile, Miguel Vioque, a researcher at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), was exploring another piece of the puzzle. Using data from Gaia, he discovered that MP Mus was 'wobbling.'

Using a combination of observations from Gaia and ALMA and computer modeling, the researchers concluded that the oscillations were likely caused by a gas giant (less than 10 times the mass of Jupiter), orbiting the star at a distance of 1-3 times the distance from Earth to the Sun.

' Our model shows that if you put a giant planet in the newly discovered cavity, you can also explain the Gaia signal ,' Ribas said. ' And using ALMA's longer wavelengths allowed us to see structures that were previously unobservable .'

This is the first time an exoplanet embedded in a protoplanetary disk has been indirectly detected by combining precise stellar motion data from Gaia with deep disk observations. This also means that many other hidden planets may exist in other disks, waiting to be discovered.

Dr Ribas said upcoming upgrades to ALMA and future telescopes such as the Next Generation Very Large Array (ngVLA) could be used to peer deeper into many protoplanetary disks, helping to better understand the hidden population of young planets – and thus how our planet formed.

You should read it

- ★ Found the second planet of Proxima Centauri, the star closest to the sun

- ★ Cosmic Science: The star system TRAPPIST-1 does not 'exist' the big Moon

- ★ The mysterious 9th planet could be a 'free floating' planet

- ★ Hot Jupiter is being torn apart by its host star

- ★ Scientists are observing an extremely rare phenomenon of a planet being swallowed by a star.