Breakthroughs in image sensors enable the viewing of ultrafine details from a distance.

A lensless imaging system, combined with processing software, has enabled scientists to observe finer details from greater distances than any traditional optical system has ever been able to achieve.

Imaging technology has long changed the way humans explore the world, from mapping distant galaxies with radio telescopes to observing the microscopic structures inside living cells. However, a major limitation remains: in the visible light spectrum, capturing images with both high detail and a wide field of view requires bulky lenses and extremely precise physical adjustments, making many applications difficult or impossible to implement.

Researchers at the University of Connecticut (UConn) believe they have found the solution to this problem. A new study by Guoan Zheng, professor of biomedical engineering and director of UConn's Center for Biomedical Innovation (CBBI), and his colleagues has introduced a completely new imaging strategy that promises to significantly expand the capabilities of optical systems in scientific, medical, and industrial research.

Why is using a synthetic aperture ineffective in visible light photography?

" At its core, this breakthrough solves a long-standing technical problem, " Zheng said. Synthetic aperture imaging – the method that helped the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) capture images of black holes – works by synchronously combining data from multiple sensors placed far apart to simulate an extremely large aperture.

This approach is highly effective in radio astronomy because radio waves have long wavelengths, making synchronization between sensors possible. Conversely, visible light has extremely short wavelengths, requiring near-absolute physical precision when aligning sensors. This is a major obstacle that makes traditional optically synthesized aperture systems difficult to apply in practice.

When the software takes on the role of synchronization.

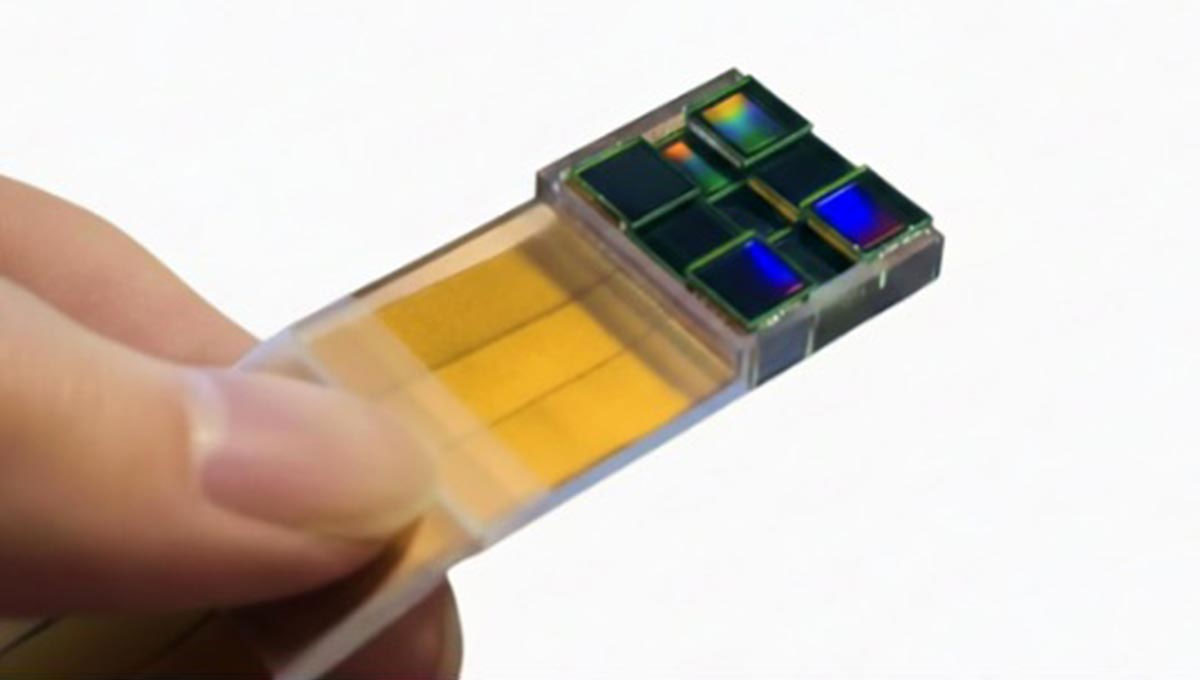

The new system, called Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI), addresses the problem in a completely different way. Instead of requiring the sensors to be perfectly synchronized during the measurement process, MASI allows each optical sensor to collect data independently. Alignment and synchronization are then performed later using an algorithm.

Zheng likened this approach to multiple photographers observing the same scene. Instead of taking conventional photos, each person records raw information about the behavior of light waves. The software then combines this independent data into a single, highly detailed image.

Computational phase synchronization eliminates the need for rigid interferometer systems – a factor that had previously hindered the popularization of synthetic aperture photography in optics.

How does MASI capture and reproduce light?

MASI differs from traditional optical systems in two key ways. First, it doesn't use lenses to focus light. Instead, the system uses an array of encoded sensors, placed at various locations in the diffraction plane. Each sensor records diffraction patterns, describing how light waves propagate after interacting with an object. These patterns contain information about both the amplitude and phase of the light, which can then be recovered computationally.

After reconstructing the complex wavefield from each sensor, the system digitally expands the data and propagates the wavefield back to the object plane. An algorithmic phase synchronization process continuously corrects the phase discrepancies between the sensors. This repetition increases coherence and focuses energy into the final composite image.

This software optimization step is the core breakthrough, enabling MASI to overcome diffraction limitations and many physical barriers that previously dominated traditional optics.

Virtual aperture, extremely high detail.

The end result is a virtual composite aperture that is far larger than any single sensor. This allows the system to achieve sub-micrometer resolution while maintaining a wide field of view, completely eliminating the need for lenses.

In traditional systems like microscopes, cameras, or telescopes, engineers always have to trade off between resolution and working distance. To see fine details clearly, the lens often has to be placed very close to the object, sometimes only a few millimeters away. This limits accessibility, reduces flexibility, and can even be invasive in some applications.

MASI overcomes this constraint by acquiring diffraction patterns from distances measured in centimeters, yet still reproducing images with sub-micrometer detail. Zheng compares this to being able to observe the microscopic grooves on a strand of hair from across the desk, instead of having to bring it up close to your eye.

Widely applicable, easily scalable.

According to Zheng, the potential applications of MASI extend from forensics, medical diagnostics, and industrial inspection to remote sensing. Most notably, its scalability is remarkable. Unlike traditional optics, which become exponentially more complex with scale, this system evolves linearly, opening up the possibility of building large sensor arrays for applications not yet fully conceived.

MASI represents a pivotal shift in optical imaging system design. By separating data acquisition from synchronization and replacing bulky optical components with software-controlled sensor arrays, this work demonstrates that computation can overcome decades-old physical limitations. It opens the door to a new generation of imaging systems: more detailed, more flexible, and far more scalable than previously thought possible.

You should read it

- ★ Do you choose a large aperture or a large sensor when taking photos?

- ★ Samsung launches revolutionary 200MP camera sensor

- ★ 3D ultrasound fingerprint sensor under Qualcomm's first screen in the world

- ★ Turn on the secret of long exposures in photography

- ★ Learn about aperture in digital photography