What 100 years of quantum physics has taught us about reality - and ourselves

This year, according to UNESCO, is the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology , marking 100 years since quantum mechanics was proposed. Yet the theory hardly needs any further promotion.

Look at the trending articles in any science magazine, and chances are quantum stories will be at the top. Cute animals aside, quantum physics is probably the most popular cover subject among science fans . But why?

A science journalist with a background in physics once said that this question is fascinating. What is hard to understand is why the public is so fascinated by quantum physics — a field that is notoriously difficult to explain and even harder to relate to everyday experience. Yet what might be called a ' quantum obsession ' has existed almost since the theory's inception.

While researching the enduring appeal of quantum physics for my master's thesis in science communication, I turned to the archives of Scientific American for answers . The oldest continuously published magazine in the United States, with a history of 180 years, is one of the few publications old enough to have witnessed the birth of the quantum era and played a role in introducing it to the public.

Over the course of several months, we have combed through the archives to find articles that contain any mention of the word quantum over 100 years of print publication. By analyzing who wrote these articles, how they chose their topics, and how they conveyed a quantum world that is often confusing to the general reader, the goal is to find out what makes quantum physics so appealing to the general public.

And the results show that the very factors that made the founders of quantum physics find it difficult to accept are what appeal to us today.

The Origin of Quantum

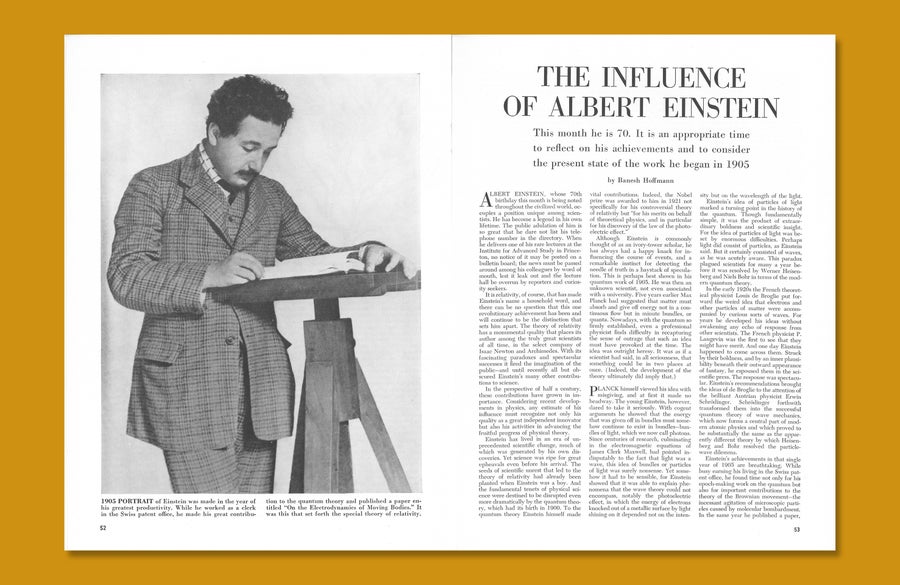

Sometimes quantum mechanics seems pitiful: the minds that laid the foundations for it were also its most vocal skeptics and critics. In 1905, Albert Einstein first popularized the concept of quanta —borrowed from the Latin word for 'how many'—to describe light as being made up of discrete packets or bundles of energy, now called photons.

At first, quantum theory asserted a seemingly simple fact: energy does not come continuously but in discrete units. But even that basic concept was controversial, because previous experiments had shown that light in many cases behaved like a wave.

Even renowned scientists struggle to communicate quantum physics to the public, a major departure from the conventional notion that scientific language can directly reflect the real world.

For example, Newton's first law of motion describes how an object will continue to move in a straight line at constant velocity unless acted upon by an external force. Here, mass is viewed as an objective entity with well-defined and measurable properties.

But when we move to quantum mechanics, things get a little more complicated. If we use the same set of equations to describe light as we do for waves, does that mean light is actually a wave — like seismic waves or water waves? If so, how can it also be a particle?

In quantum mechanics, even the notion of cause and effect is challenged: instead of deterministic relationships as in Newton's laws, we must accept the laws of probability . This has often left the very creators of the theory bewildered as they sought to interpret it.

Physicist John Gribbin , author of In Search of Schrödinger's Cat: Quantum Physics and Reality (1984) , once described that early period as a place of intellectual chaos. ' Part of the appeal of quantum mechanics,' he wrote, 'is that it is so incomprehensible that it is almost magical. '

This feeling is not unique. In a 1949 article praising Einstein, the British mathematician and physicist Banesh Hoffmann called quantum mechanics 'heretical'. The term reflected a deep discomfort with concepts such as the possibility that a particle could exist in two places at once. Even Einstein, who laid the foundations for the theory, rejected its probabilistic nature, famously saying: ' God does not play dice ' .

The Quantum Age has arrived

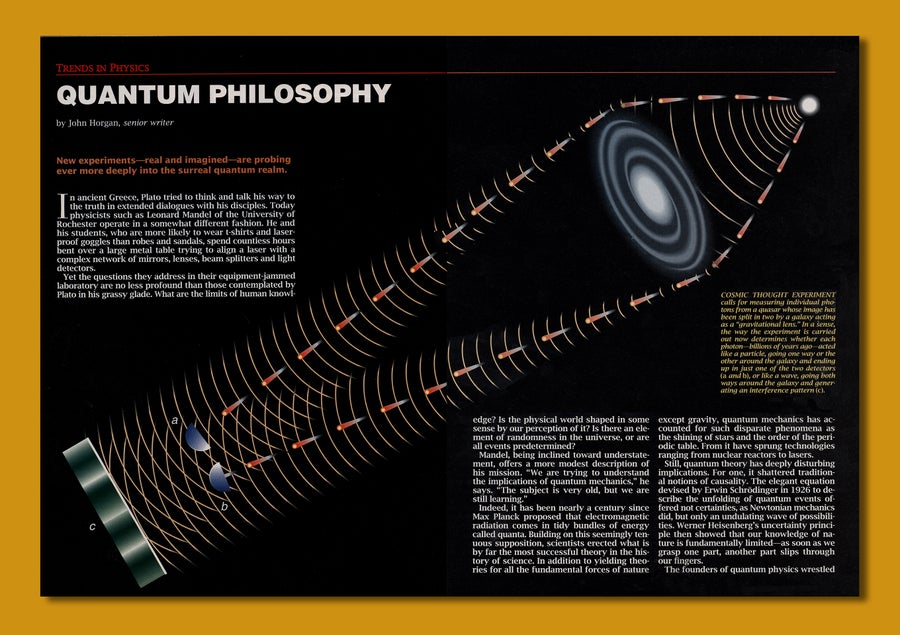

The ambiguity and controversy surrounding quantum mechanics may have helped it gain traction in its early years, but that level of interest paled in comparison to what would follow in the decades that followed. In Scientific American , the number of articles on quantum mechanics more than tripled between 1960 and 1980 compared with the previous 20 years. Most were written by a new generation of scientists who had received formal training in quantum mechanics in graduate school.

Historical context plays a role, with several countries competing fiercely in the race for science and technology. It was during this period that fundamental technologies based on quantum theory — from atomic clocks to lasers to the first semiconductor circuits — were born.

But as they enter everyday life, these technologies have become so ubiquitous that they are no longer considered 'quantum' in the strictest sense. Lasers are commonplace components in CD players, barcode scanners and office printers; semiconductors are hidden in countless devices, from desktop computers to laptops.

In articles on Scientific American , an interesting assumption has gradually formed: what is common and mundane is no longer 'quantum' by default. So instead of calling chips or lasers quantum technology, authors increasingly prefer to emphasize the 'strange', 'weird' and 'surreal' nature of this microscopic world.

Indeed, those are perfectly appropriate adjectives to describe quantum mechanics. The quantum world defies basic intuition and seems to overturn everything that was once taken for granted about how the universe works.

By the 1990s, quantum writings increasingly focused on questioning the ultimate nature of reality: from the hypothesis that the universe is made of tiny vibrating strings, to the idea that quantum mechanics branches into countless parallel universes, and many other bold concepts.

A search of the Scientific American archives reveals that there is no single definition of the quantum world. It is not confined to Einstein's discrete energy levels of photons, or the wave function that turns things into probabilities, nor is it confined to the non-locality and opacity of reality. Instead, quantum mechanics is a vast web of things that are still not fully grasped. Therein lies its enduring appeal: alongside the comfort of the familiar, humanity is continually drawn to the feeling of being challenged, shaken, and amazed by the mystery of the world in which we live.

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-100-years-of-quantum-physics-has-taught-us-about-reality-and-ourselves/

You should read it

- ★ Quantum computing - a marathon, not a sprint contest!

- ★ China successfully developed 'handheld' quantum satellite communications equipment

- ★ New chip technology can enhance quantum computing

- ★ Quantum computing - the future of humanity

- ★ For the first time successfully implementing underwater quantum teleportation, China took the lead in the quantum communication race