The human genome is evolving much faster than we thought.

Understanding how human DNA changes over generations is crucial for estimating the risk of genetic diseases and tracing our evolutionary history. However, until now, understanding some of the most highly variable regions of DNA has been a challenge for researchers.

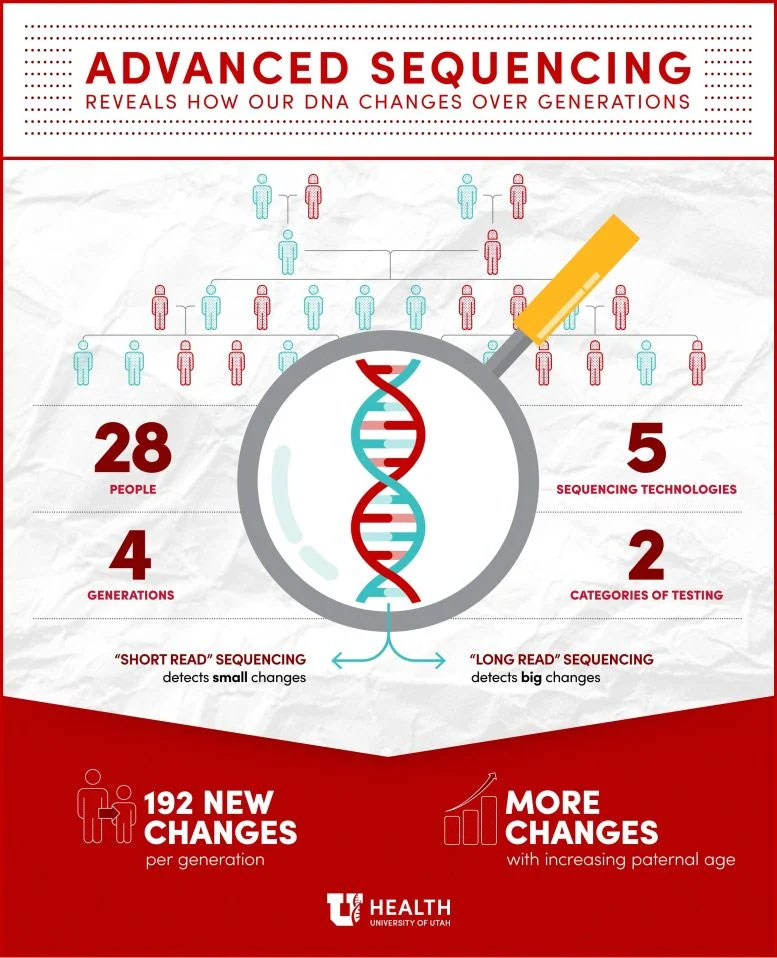

Scientists from the University of Utah School of Medicine, the University of Washington, PacBio, and other institutions have used advanced DNA sequencing technology to create the most detailed map of genetic change over generations. The study reveals that parts of the human genome change much more rapidly than previously recognized, opening the door to deeper understanding of the origins of disease and human evolution.

The "light" speed of biology

By comparing the genomes of parents and offspring, the team measured how often new mutations occur and are inherited. This mutation rate is as fundamental to human biology as the speed of light is to physics, explains study author Lynn Jorde, PhD. ' This is what we really need to know—the rate at which variation occurs in our species ,' says Jorde, a professor of genetics at the University of Utah Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine. ' All the genetic variation that we see from one individual to the next is the result of these mutations .' Generation after generation, these changes have resulted in everything from differences in eye color to the ability to digest lactose to rare genetic disorders.

Researchers estimate that each of us carries nearly 200 new genetic changes that differentiate us from our parents. Many of these changes occur in regions of DNA that are particularly difficult to study.

Previous attempts to study genetic variation in humans have been limited to the parts of the genome that mutate the least, said study co-author Aaron Quinlan, PhD, professor and chair of the department of genetics at SFESOM. But the new study used advanced sequencing technology to reveal the regions of DNA that change most rapidly in humans — regions that Quinlan described as ' previously untouchable .'

" There are parts of our genome that mutate wildly, almost every generation ," he said. " Other stretches of DNA are more stable ."

Jorde says the new resource could be an important aid to genetic counseling by helping to answer the question: ' If you have a child with a disease, is it likely to be inherited from the parents or is it a new mutation? ' Diseases caused by changes in 'mutation hotspots' are more likely to be unique to that child, rather than being inherited from the parents. This means that the risk of parents having other children with the same disease is lower. But if the genetic change is inherited from the parents, their future children will have a higher risk of developing the disease.

The researchers' discovery was based on a Utah family that has been collaborating with geneticists since the 1980s. Four generations of the family donated DNA and consented to analysis, allowing the researchers to gain an incredibly detailed look at how new changes arise and are passed from parent to child. " A large family of this size and depth is a unique and valuable resource ," said Deborah Neklason, PhD, research associate professor of internal medicine at SFESOM and co-author of the study. " It helps us understand variation and changes in the genome across generations with an incredible level of detail ."

To get a comprehensive, high-resolution picture of genetic variation over time, the team sequenced each person's DNA using a variety of technologies. Some technologies are best at detecting the smallest possible changes to DNA; others can scan huge stretches of DNA at once to find large changes and see parts of the genome that are otherwise difficult to sequence. By sequencing the same genome with multiple technologies, the researchers got the best of both worlds: precision on both small and large scales.

In the future, the researchers hope to expand their comprehensive sequencing technique to more people to see whether the rate of genetic change varies between families. ' We saw some really interesting things in this family ,' Quinlan says. The next question is, ' how generalizable are those findings across families when trying to predict disease risk or how the genome evolves? '

The sequencing results will be made freely available so that other researchers can use the data in their own studies, opening the door to deeper insights into human evolution and genetic disease.

You should read it

- ★ The human brain's small biological model reveals the effects of hallucinations

- ★ Two new frog species are named after legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick

- ★ What happens when we take medicine?

- ★ Misconceptions about biology that many people still believe in.

- ★ Robot milliDelta robot is set up with roles in production and medicine