Successfully created a type of extraterrestrial diamond at normal laboratory temperatures in just a few minutes.

A team of scientists from Australia recently successfully created two different types of diamonds – a regular diamond and a type of diamond called lonsdaleite, which is found naturally only at meteorite impact sites – in just a few minutes in the laboratory at normal temperatures. Meanwhile, creating these diamond crystals in nature would require a process spanning billions of years, along with immense pressure and extremely high temperatures.

Essentially, most gemstones are formed after carbon is crushed and heated beneath the Earth's surface for billions of years. This is why they are so rare, expensive, and highly sought after.

Among gemstones in general, diamonds are in the most valuable group – not only because of their rarity but also because of their exceptionally superior properties such as extremely high hardness, excellent thermal conductivity, and outstanding applications in quantum optics and biomedicine.

"Natural diamonds are typically formed over billions of years, at depths of around 150km beneath the Earth's surface, where pressure is high and temperatures are consistently maintained above 1,000 degrees Celsius," said Jodie Bradby, professor of physics at the Australian National University and head of the research team.

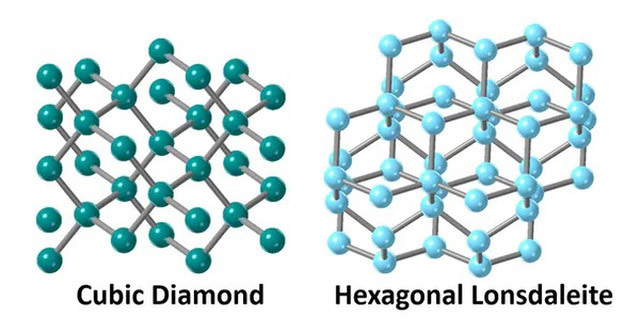

However, in a new study published on November 18th, Professor Bradby and colleagues at RMIT University (Australia) have found a way to accelerate the diamond formation process, which takes billions of years in nature, to just a few minutes, at normal laboratory temperatures. Furthermore, the scientists were able to create two types of diamonds with completely different structures: one similar to natural diamonds on Earth, and the second, lonsdaleite, also known as hexagonal diamond, which is only found on asteroids in outer space and possesses superior hardness compared to other types of diamonds.

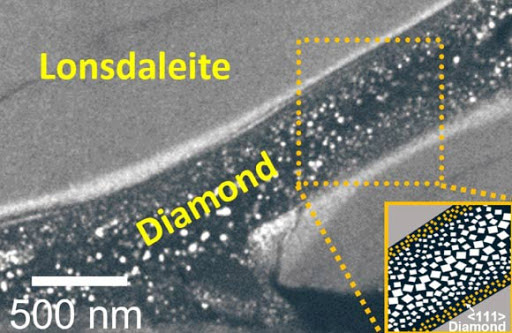

First, scientists used advanced electron microscopy techniques to photograph solid, intact slices from the test sample to create a snapshot of how nanocrystalline diamonds and lonsdaleite are formed. They found the ridges of both regular diamonds and lonsdaleite diamonds running through and intertwining with each other, thus gaining a better understanding of how they are formed.

Next, the scientists used immense pressure to create a "shear force" that caused the carbon atoms to move into the correct positions, forming lonsdaleite, just like regular diamonds.

The results showed that both lonsdaleite and ordinary diamonds can form at room temperature simply by applying high pressure levels of up to 80 gigapascals, equivalent to the weight of 640 African elephants pressing down on a ballet shoe.

"The turning point in the story is how we apply pressure ," Professor Bradby said. "By using extremely high pressure, we force the carbon to also experience something called 'shear force'—similar to torsional or shear force—to get into the right position."

This is a significant achievement. The ability to create ultra-rare materials like Lonsdaleite holds great potential for widespread application in everyday life, especially in fields requiring ultra-hard materials, such as diamonds used to coat drill bits or cutting blades to extend the lifespan of these tools.