Scientists discover traces of ancient life in an unexpected place.

Dr. Rowan Martindale, a paleontologist and biogeologist at the University of Texas (USA), was walking through the Dadès Valley in the Middle Atlas Mountains (Morocco) when an unusual detail on the rocks made her stop. At that time, Martindale and her research team, including Stéphane Bodin from Aarhus University, were surveying the ecosystem of ancient coral reefs that once lay deep beneath the sea.

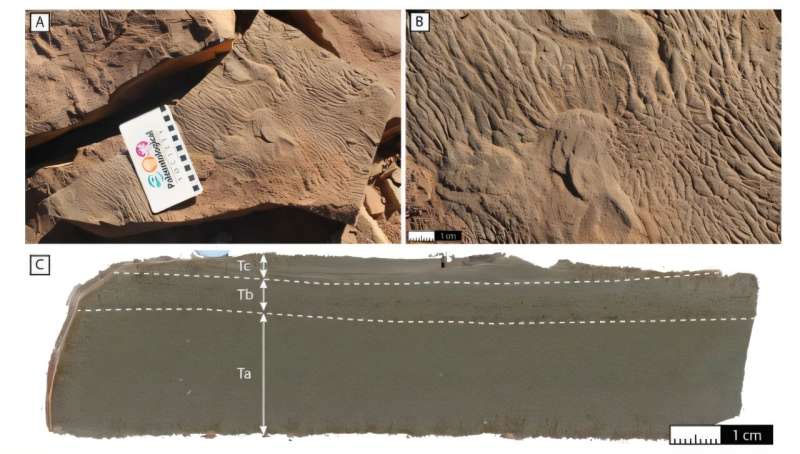

To reach the area that was once a coral reef, they had to traverse layers of turbidite – sediments formed from powerful currents of mud and debris at the bottom of the ocean. Turbidite typically retains familiar ripples, but Martindale noticed something unusual superimposed on these ripples. The rock's surface had small, uneven wrinkles and bumps, completely unlike what she had expected.

Unexpected patterns in the stone

" As we walked along the layers of turbidite, I noticed one side of the layer had some very beautiful ripples ," Martindale recounted. "I called Stéphane over right away and said, ' Look, these are wrinkle structures! '"

Wrinkle structures are small ridges and shallow pits, ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters, that form on sandy seabeds when algae or microorganisms develop into biomats or clumps. These fragile structures are often swept away when animals stir up the sediment.

Therefore, they are rarely found in rocks younger than about 540 million years old – the time when animal life exploded and began to violently disturb the seabed surface. In modern environments, wrinkled structures are usually associated with shallow tidal zones, where sunlight is sufficient for photosynthetic algae to thrive.

The problem is that the turbidites Martindale is studying formed at a depth of at least 180 meters, where sunlight cannot penetrate. This almost rules out the possibility of photosynthetic algae – the familiar 'culprit' behind today's wrinkles. Previous reports of wrinkles in ancient turbidite sediments have also been questioned, further fueling the controversy surrounding this discovery.

Furthermore, these rock formations are only about 180 million years old, a time when the seabed habitats have been heavily disturbed by animals, making the preservation of such delicate structures highly unlikely. Every element of the geological context suggests these patterns 'shouldn't exist,' and Martindale understood that he had to verify all the evidence with extreme caution.

'We had to examine each piece of evidence one by one to be sure this really was a wrinkled structure within turbidite,' Martindale said, because structures of photosynthetic origin like this 'shouldn't be present in such a deep water environment.''

Hypothesis testing

Once the research team confirmed the sedimentary layers were indeed turbidite, the next step was to prove that the observed patterns were actually of biological origin. Analysis revealed that the rock layers directly beneath the folds had unusually high carbon content – a typical sign of biological activity.

Additionally, videos recorded by remotely operated submersibles at the seabed, below the illuminated areas, show that microbial mats can still form thanks to chemosynthetic bacteria. These are bacteria that obtain energy from chemical reactions, rather than sunlight.

By combining geological, chemical, and similar examples from modern environments, the research team concluded that they had observed crease structures created by chemosynthetic organisms within the rock profile. Turbidite flows carry nutrients and organic matter, reducing oxygen concentrations and creating conditions favorable for chemosynthetic life.

During the quiet periods between turbidite depositions, bacteria grow into mats on the sediment surface, subsequently forming the characteristic creases observed by Martindale in Morocco. Usually, the next turbidite layer washes these mats away, but sometimes, they are rarely preserved within the rock.

The significance for the search for ancient life.

In the future, Martindale hopes to conduct lab experiments to understand in more detail how these structures form in the turbidite environment. She also hopes that this discovery will encourage other researchers to broaden their perspective, incorporating chemosynthetic microbial mats into a model that previously only acknowledged a photosynthetic origin for the wrinkled structures.

At that point, geologists could begin searching for traces of life in environments previously considered 'hopeless' in the quest for the earliest signs of life on Earth.

" The wrinkled structures are incredibly important evidence in the early evolution of life ," Martindale emphasized. If we ignore the possibility of their existence in turbidites, " we may be missing a crucial piece of the history of the microbial world ."

You should read it

- ★ How Alien Life Exists Without Water

- ★ A terrifying object that made life on Earth evolve by leaps and bounds?

- ★ Suddenly discovered life right in the core of the Earth

- ★ Deep-sea rocks on Earth spark new hope for finding life on Mars

- ★ If people 'occupy' the Sun 2.0 system, how different is life there from Earth?