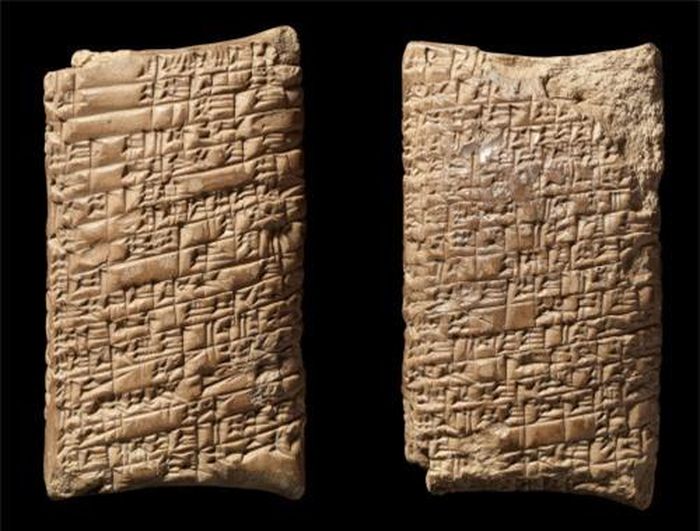

4,000 year old sales complaint letter

Complaint plaque addressed to Ea-nāsir (UET V 81). The palm-sized clay tablet (11cm high, 5cm wide, 2.6cm thick) inscribed with cuneiform dating from 1,750 BC, indicates that customer Nanni ordered copper ingots of the merchant Ea-nāsirbut they were substandard and not accepted, even though payment had been made.

This famous letter was discovered in the ancient city of Ur in southern Iraq in 1930-1931, when an expedition led by archaeologist Leonard Woolley unearthed a series of business documents written in cuneiform on it. small clay slabs.

According to the letter, a businessman or artisan named Nanni criticized merchant Ea-Nasir for promising to sell him 'copper ingots of good quality' but then failing to comply with the agreement.

Nanni was upset that the merchant had sent low-grade copper ingots and treated him and his messenger with contempt – apparently only because he still owed him 'a (common) mina of silver' in when on his behalf he brought to the palace 1,080 pounds of copper and the umi-abum also brought 1,080 pounds of copper, besides what they had written on the clay tablet sealed and kept in the Samas' temple (a mina is about 1/5 pound)

When Nanni's messenger tried to argue with Ea-nāsir about the quality of the copper ingot, Nanni wrote that he was ignored. 'If you want it, take it. If not, then go away', Ea-nāsir is said to have said to the young man.

Nanni was very angry, both about the quality of the copper ingot and the merchant's attitude towards his news. The messenger had to return empty-handed many times and each time had to cross dangerous enemy territory. Nanni demanded his money back and ended the letter with a blunt statement: 'I will not accept any of your substandard copper ingots. [From now on, if you want to sell to me, you will have to bring copper to me.] I will choose each ingot on my yard and will use my right to refuse to accept the goods because you have despised me. '

For archaeologists who study metal production and exchange in the ancient Near East like Professor Lloyd Weeks at the University of New England (Australia), the letter captures the miniature reality of an economy. ancient.

The copper metal that Nanni mentioned can be used to make important everyday items such as tools, containers, and cutlery. Therefore, it was an important commodity in Bronze Age Mesopotamia. At this time, Ur was a powerful Sumerian city-state located on the Persian Gulf and an important center in a vast trading network. But because Ur was not rich in metals, traders had to find copper more than 600 miles away at Dilmun, on an island now called Bahrain, GS. Weeks explains.

The Ea-Nasir tablet reassures the two men (UET V 72). In this unpublished clay tablet, Ea-Nasir and his associate Ilushu-illassu write letters to several men to reassure them. Despite lacking clear context, the letter revealed that there was an 'incident' with someone they called Mr. Shorty (kurûm), and if this person comes, do not show fear. Ea-Nasir complained that people did not believe him and repeatedly reassured his colleagues: 'Don't be afraid!' 'Don't criticize!' 'Do not worry!'. Photo: Mostly Dead Languages

To be able to afford expensive trips, private traders have banded together to raise capital to buy copper from outside. Each person contributed capital in the form of different commodities, such as silver and sesame oil. These joint ventures would then sell the copper and divide the proceeds among themselves, while also paying tithes and other taxes to the palace and (possibly) the temple. In his letter of complaint, Nanni mentions the payment of 1,080 pounds of copper to the palace - evidence of Sumerian royal tithing.

Bound together by class ties, personal reputations, and the need for interdependence, this early globalized economy had a startling complexity – and it was all due to the traders such as Ea-nāsir and Nanni took charge.

GS. Weeks comments: 'People often talk about globalization as a modern phenomenon. But the Bronze Age is often the first period in which archaeologists and economic historians feel they can look at the impact of globalization. It may not have covered the entire globe but it stretched across vast areas of the Eurasian continent at that time.'

Returning to Ea-nāsir, it turned out that he was a notorious trader. Nanni wasn't the only one to complain against him. In fact, the British Museum also stores much evidence of Ea-nāsir's crooked dealings. On another clay tablet, a person named Imgur-Sin shouted that Eà-nāsir must 'transfer good quality copper to Niga-Nanna. Must give him good quality copper so that I will not be bothered! Don't you know that I'm very tired?'. In another declaration to the copper tycoon, a merchant named Nar-am demanded of him: 'You must give Igmil-Sin [Nar-am's messenger] good copper! Hopefully you still have good coins in your hand.' Ea-nāsir's reputation for poor quality products was evident in the city of Ur.

With such poor customer service, let's give Ea-nāsir a chance to have the last word. Luckily, a clay document from this Babylonian merchant still exists - and not surprisingly, it's full of drama. In a cuneiform letter, Ea-nāsir told a man named Šumum-libši and a bronzesmith not to overreact when two other men came to them looking for some lost metal. Ea-nāsir advised them: 'Don't criticize or discuss it'. 'Do not be afraid!'. What solid advice from history's most famous copper scammer.

You should read it

- ★ Do air conditioners need to change copper pipes?

- ★ Why use standard copper conduit?

- ★ Why are cartridges usually made of copper and not steel, lead or aluminum?

- ★ Turn copper into a material that closely resembles gold

- ★ Peru's first satellite provides a panoramic view of the large copper mine in the Andes